February 18, 2014

5 February 2014

A global study by Tasmanian researchers shows what is needed to make marine parks effective, the findings of which were published in Nature.

In collaboration with overseas investigators and skilled recreational divers, University of Tasmania biologists, including researchers from the NERP Marine Biodiversity Hub, counted numbers and sizes of more than 2000 fish species along underwater transect lines set at 1986 sites in 40 countries. They then used this information to measure how fish communities in 87 marine protected areas (MPAs) worldwide differed from those in nearby fished areas.

The New York Times commmented that "One of the few bright spots in the struggle to protect the world’s fragile oceans has been the rapidly increasing number of “marine-protected areas,” places where fishing is limited or banned and where, presumably, depleted species can recover by simply being left to themselves. The benefits of hands-off environmental protection may seem self-evident. But creating a preserve and rebuilding a healthy ecosystem are not necessarily the same thing. A recent study published in Nature found that, more often than not, marine-protected areas don’t work as well as they could."

Further information

- Nature article Edgar GJ, Stuart-Smith RD, Willis TJ, Kininmonth SJ, Baker SC, Banks S, Barrett NS, Becerro MA, Bernard ATF, Berkhout J, et al. Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature [Internet]. 5 Feb 2014

- "To save fish and birds" New York Times editorial, 15 February 2014

- Reef audit finds big fish lost, The Age, 21 February 2014

- Study shows many marine protection zones aren't protecting fish, ABC News, 6 February 2014

- Researchers map life under the sea, The Mercury, 20 February 2014

- Media release, University of Tasmania, 6 February 2014

Image

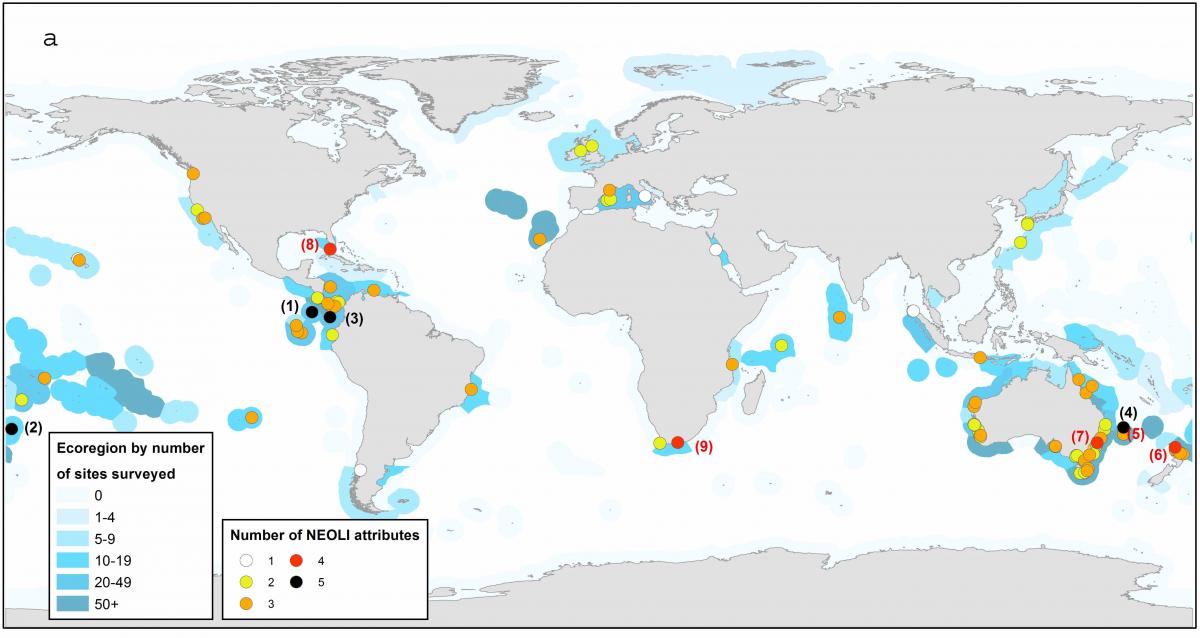

Extended Data Figure 1 | Distribution of sites surveyed. a, Number of NEOLI (no take, enforced, old, large and isolated) features at MPAs investigated (coloured circles). MPAs with most NEOLI features are overlaid on top; consequently numerous MPAs with one and two features are not visible. MPAs with five NEOLI features are (1) Cocos, (2) Kermadec Islands, (3) Malpelo, (4) Middleton Reef; MPAs with four NEOLI features are (5) Elizabeth Reef, (6) Poor Knights Islands, (7) Ship Rock, (8) Tortugas and (9) Tsitsikamma.

Contact

- Log in to post comments