June 18, 2018

An Indigenous engagement workshop held at the 2017 Australian Marine Science Association (AMSA) Conference at Darwin in July shared successes and identified pathways to meaningful collaboration in sea-country research.

The workshop, held on the traditional lands of the Larrakia people, was sponsored by the Marine Biodiversity Hub and Parks Australia, and followed the first Hub-sponsored Indigenous engagement workshop held at the 2016 conference in Wellington, New Zealand.

Representatives from the Northern Land Council, Parks Australia, the North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance Ltd, the Australian Institute of Marine Science, the Marine Biodiversity Hub and CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere worked together to make the 2017 event a great success.

It attracted more than 100 researchers and practitioners (including Indigenous Sea County rangers) from Traditional Owner groups, Indigenous land councils and not-for-profit organisations, fisheries and government agencies, and universities.

After an opening address by Hub deputy director and organising committee member, Paul Hedge, workshop presentations and discussions explored the ways Indigenous communities are engaging in marine science around Australia.

‘Engagement is an important topic with many considerations, and the need for research partnerships built on mutual trust, respect and understanding is clearly articulated in numerous documents, such as Indigenous Protected Area plans, Healthy Country plans and Sea Country plans and engagement protocols’ Mr Hedge said

‘There is a growing demand for Indigenous practitioners to lead sea country research, and an increasing understanding that Traditional Owners should be appropriately recognised and remunerated for their involvement in collaborative projects.

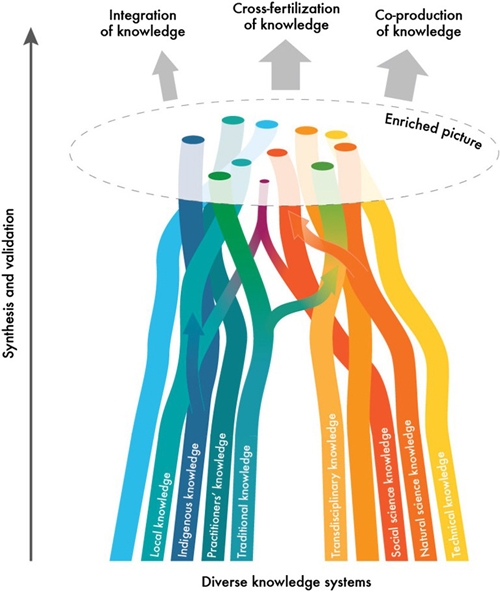

‘Some of the key ingredients discussed included early engagement with Indigenous communities to understand their interests and needs, following appropriate protocols, investing in long-term collaborations, and recognising the research value of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives.’

A workshop summary captures key learnings and insights from the presentations and panel discussion, and includes links to a rich collection of resources. Here are some of the highlights.

Key considerations for marine researchers engaging with Indigenous communities

Take time to understand the community

Determine whether your research interests overlap with Native Title or Indigenous Protected Area plans or local research priorities and seek to understand the local Indigenous governance and whether there are local Indigenous engagement protocols.

Engage with community leaders

Understanding the community’s needs, interests and capacity will take time and should not be rushed. If for some reason you do not engage early, it is not too late, but do not expect a warm response immediately; apologise and learn from your mistake and seek to move forward in a mutually acceptable and respectful manner.

Negotiate a research agreement

Once research interests are clear and a project plan has formed, always negotiate a detailed research agreement with the Indigenous community (and renegotiate substantial changes). These should refer to things such as: a code of conduct, intellectual property, engagement and feedback milestones and culturally appropriate communication outputs. It critical to ensure a fast payment system and good communication plan that includes time and resources for face-to-face interactions. Trust is a critical element of forming the agreement and in some cases communities may seek the right to veto research results; seek to understand why.

How can the research community enrich Indigenous engagement in marine science?

Be professional

Marine scientists must be as committed and professional when engaging with Indigenous communities as they are with other groups that hold rights and have interests in the marine environment (such as commercial fisheries and the oil and gas industry). This includes recognising rights and needs, staying engaged and investing resources, and understanding how research can benefit communities in different ways.

Put it in policies

Acknowledge and include Indigenous values and interests in high-level policies and strategies that direct Australia’s marine research, such as in Australia’s National Marine Science Plan.

Pool and share

Collate and provide accessible information to support the development of cross-cultural research, in particular with easy to access information that helps researchers identify interests and make decisions about engagement. For example, collating maps of Sea Country, Indigenous Protected Areas and Native Title and practical documents such as engagement guidelines and protocols and templates for research agreements and communication plans. Maintaining lists of researchers with Indigenous engagement expertise and funding opportunities that could be used to support engagement may also help researchers.

Celebrate excellence

Acknowledge and encourage excellence and commitment of Indigenous people to good marine science through the awarding of prizes or scholarships by Australia’s marine research institutions and associations such as CSIRO, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Australian Marine Sciences Association, the Australian Society of Fish Biology, the Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society and the Australian Coral Reef Society.

Case study presentations

1. Working together to satellite-track dugongs and turtles in the Torres Strait

Helene Marsh, James Cook University and Frank Loban, Torres Strait Regional Authority

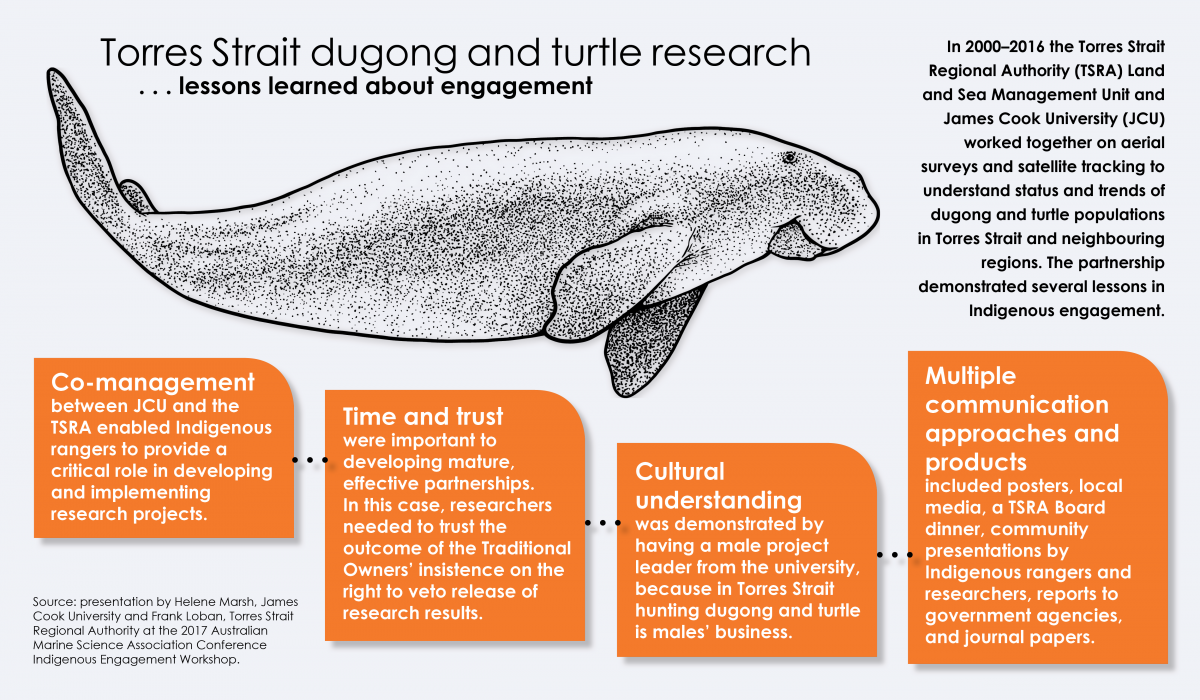

In 2000–2016 the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) Land and Sea Management Unit and James Cook University (JCU) worked together on aerial surveys and satellite tracking to understand status and trends of dugong and turtle populations in Torres Strait and neighbouring regions. The partnership demonstrated several lessons in Indigenous engagement.

- Time and trust were important to developing mature, effective partnerships. In this case, researchers needed to trust the outcome of the Traditional Owners’ insistence on the right to veto release of research results.

- Cultural understanding was demonstrated by having a male project leader from the university, because in Torres Strait hunting dugong and turtle is males’ business.

- Co-management between James Cook University the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) enabled Indigenous rangers to provide a critical role in developing and implementing research projects.

- Multiple communication approaches and products included posters, local media, a TSRA Board dinner, community presentations by Indigenous rangers and researchers, reports to government agencies, and journal papers.

Presentation: A learning experience: engaging traditional owners in dugong research in Torres Strait

2. Building researcher engagement with the Yirrganydji Rangers in the Cairns region of the Great Barrier Reef

Gavin Singleton, Yirrganydji Land and Sea Ranger

In the past three to four years, Yirrganydji Land and Sea Rangers have been working with a range of researchers on various collaborative projects including seabird monitoring, crocodile management and hammerhead shark tagging.

The Sea Country Plan has been an important document for collaboration as it captures information on research interests and priorities. See Yirranganydji Sea Country Plan

3. Malak Malak Country, sawfish country

Aaron Green, Malak Malak Rangers, Rob Lindsay, Malak Malak Rangers and Christy Davies, North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance Ltd

Malak Malak Rangers worked with the North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance and Charles Darwin University to improve understanding of the status of Largetooth Sawfish and other river sharks in Northern Australia and support culturally appropriate, locally driven conservation.

These presenters emphasised the importance of budgeting for and producing a variety of communication products, including products based on community advice and locally-driven. Read more about the posters, videos, field protocols, reports and educational signage produced by this Marine Biodiversity Hub project.

Presentation: Malak Malak country, Sawfish country: Indigenous partnerships for management of euryhaline species.

Save a Sawfish animated video

Education materials including videos, signage and relocation protocols were produced by a Marine Biodiversity Hub project led by Charles Darwin University and under the guidance of the North Australian Indigenous Land and Sea Management Alliance Ltd. The Save a Sawfish video above is part of this package, and shows how sawfish should be released after being accidentally caught on a line or in a net. The video is availabe in English and Kriol.

4. Kimberley Marine Research Program

Daniel Oades, Kimberley Land Council and Stuart Field, Western Australian Marine Science Institution (WAMSI)

Traditional Owners and Indigenous ranger groups worked with managers and researchers from WAMSI on an integrated program of marine research for the Kimberley region. The Kimberley Marine Research Plan had 25 individual projects, one of which was the Kimberley Indigenous Saltwater Science Project.

Presentation: Kimberley Marine Research Program

5. Cultural Leadership in Coastal and Marine Management Research: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach

Doc Reynolds, Tjaltjraak and Richard Campbell, Northern Land Council

The Esperance Tjaltjraak Circle of Elders (though a cultural coordinator) has worked with science institutions for more than a decade on multi-disciplinary research projects including mutton birds, white sharks, Australian sea lions, vegetation and archaeological sites.

Presentation: Cultural Leadership in Coastal and Marine Management Research: A multi-disciplinaryapproach - A Case Study from Tjaltjraak Country (southern Western Australia)

6. Guidelines and ethical standards for engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in marine research

Chrissy Grant, Aboriginal (Eastern Kuku Yalanji) and Torres Strait Islander (Mualgal from Moa Island) Elder

A good practical starting point for inexperienced marine researchers and science managers is the Australian Institute of Torres Strait and Islander Studies Guidelines for ethical research in Australian Indigenous Studies. Other useful guidelines are listed below.

- Ask First – A guide to respecting Indigenous heritage places and values

- NHMRC – Ethics and Values – Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research

- Our culture – Our future. (A report on Australian Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights)

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- UNESCO Policy on engaging with Indigenous peoples – in development

Presentation: Ethical standards for research impacting on aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

- Log in to post comments