October 17, 2014

A study of deep-sea habitats off Western Australia is continuing to build lasting benefits for the nation, providing knowledge and tools for marine environmental planning and management. In 2005, scientists took the Marine National Facility Research Vessel Southern Surveyor to explore areas of continental shelf and slope (200–1,500 metres depth) between Dampier and Albany. Their findings have been used to:

- define distribution patterns of habitats and seabed fauna;

- confirm Provincial boundaries used in marine bioregional planning that had been largely based on fish species;

- develop tools for identifying priority conservation areas; and

-

address marine biodiversity questions on a global scale.

‘Australia’s deep continental margin makes up almost half of our nine-million-square-kilometre marine estate, yet little is known about its habitats and fauna,’ Marine Biodiversity Hub director, Nic Bax says. ‘Voyages such as these make large contributions to the broad-scale ecosystem research required to manage the sustainable use of marine resources at a national scale. A decade on, the data collected during this voyage have already produced more than 28 scientific papers, and are still being used in multiple projects.’

High diversity revealed

The WA voyage targeted complex habitat types such as deep reefs and submarine canyons, in areas of high management priority. The seabed was surveyed using multi-beam sonar and towed cameras, and nets and sleds sampled the habitats and fauna. Seabed maps, images and samples revealed spectacular structures, (such as the Perth Canyon, a submarine gorge comparable in size to the Grand Canyon), and provided details of their diverse marine life and ecological processes.

Since the survey, many years have been devoted to characterising the biological collections, in many cases to species level, and to integrating the data at appropriate scales for scientific modelling and management planning. ‘Our challenge has been to understand ecosystem structure and processes at the fine scales seen on the voyage, then expand this knowledge to landscape scales for management purposes,’ Alan Williams of CSIRO says. For example, we saw that currents operating for millennia have allowed tropical fauna to co-exist with more temperate forms, and that species distributions are linked to environmental factors at distinct depths, such as temperature, oxygen and salinity. ‘Knowledge such as this is relevant to planning and management because it provides understanding about ecosystem structure and function and insights about the suite of conservation measures, beyond marine reserves for example, required to conserve marine biodiversity.’

Predictive modelling

In 2012, statistical modelling based on data from the WA voyage fed into the planning process for determining the boundaries of Commonwealth marine reserves around Australia.

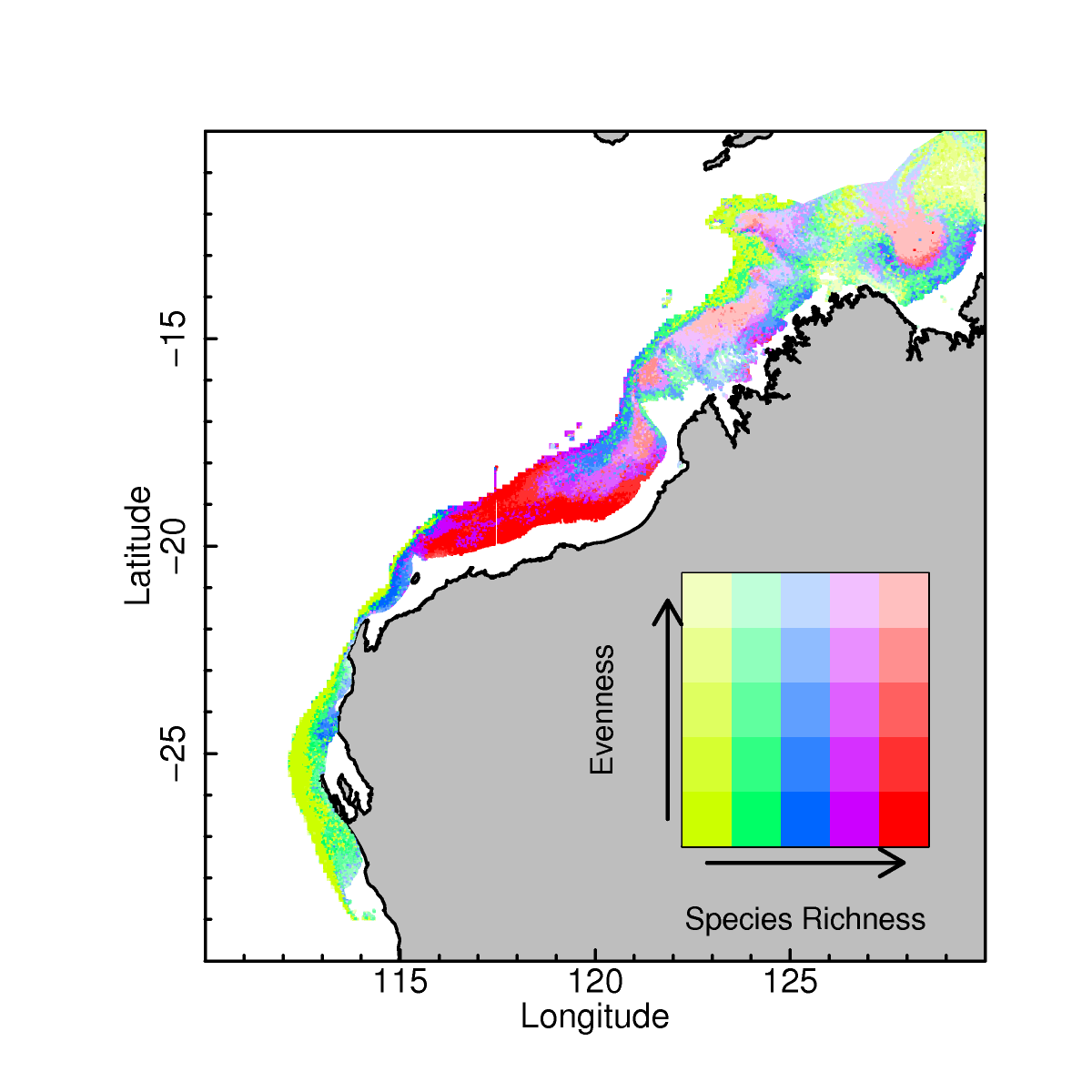

‘The ability to predict into areas where data are sparse and identify areas of interest is an important management step, in both marine and terrestrial environments,’ Piers Dunstan of CSIRO says. The approach, Rank Abundance Distributions, allowed us to target conservation management at species that would otherwise be missed. We combined faunal distributions and environmental data to identify areas with high numbers of rare species and species assemblages, in more detail than is possible based on species richness alone. The modelling demonstrated an enormous amount of variability in species structure on the continental shelf and slope and species such variation over short distances, and the approach has been applied nationally with other datasets. The voyage was key to understanding the structure of communities and to providing insights about conserving marine biodiversity in these areas, such as placement of boundaries for marine protected areas and different options for conditions on development permits.’

Reading the sands

Inventories of smaller faunal species found off WA have helped to shape ‘species accumulation curves’ suggesting that global species richness, and the level of undescribed marine fauna, is much higher than previously thought. Much less is known about these tiny fauna that live among the sand grains, because they are so numerous, and because the identification process may necessitate microscopy, dissection, checking international records, and consultation with overseas taxonomists.

An international team led by Museum Victoria’s Gary Poore found that 95% of crustacean species were undescribed, 72% of polychaetes were new to the Australian record, and most species were rare. Similar data are likely for the largely unexplored bathyal regions (below 200 metres),’ Gary says. ‘From this we conclude that the numbers upon which previous extrapolations to larger areas are based are too low to provide confidence.’ Gary says a further accumulation of species is likely as more deep sea regions are explored.

‘The Southern Australian and Indo-West Pacific deep-sea regions contribute significantly to global species diversity, yet these regions, as well as bathyal and abyssal habitats, are poorly sampled, he says. ‘Other factors contributing to a higher species tally include the high species richness of infaunal (small, substrate-living) taxa compared with larger taxa, and the unacknowledged endemism among cryptic and undescribed species.

‘Data from the WA voyage and other remote regions, and the lack of faunal overlap, suggest that the world’s undescribed marine fauna is probably close to 90%, and therefore much higher than previous estimates of between one-fifth and two-thirds.’

Sustained national benefit

Taxonomists at Museum Victoria advise that the faunal collection from the WA voyage is available for further taxonomic, evolutionary and biogeographic research, with the potential for multiple PhD projects to be based on identifying material to species level. Thus the research outputs from this voyage are expected to continue.

‘Voyages such as this provide lasting benefit to the nation, but can fail to pique the interest of research allocation bodies because they may lack short-term, high-profile outputs,’ Nic Bax says. ‘We need to improve the use of the national infrastructure to support the longer term interests of the Australian Government. ‘One way of doing this is to show the long-term value of well-designed surveys that involve geological, ecological and taxonomic experts planning collaboratively with resource managers.’

The Voyage of Discovery was sponsored by CSIRO, the National Oceans Office and the Marine National Facility. It included scientists from CSIRO, Geoscience Australia, the Western Australian Museum, the Australian Museum, Museum Victoria and the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory.

Hermit crabs indeed

Hermit crabs are notoriously difficult to identify, so the taxonomic sorting of five hermit crab families collected during the WA voyage was no mean feat. Hermit crabs form part of the leggy assortment of 524 pink, red and cream-coloured decapod species collected. Of this total, one third is suspected to be new to science, 8% new for Australia, and 25% new to southern WA. For these results 188 original research papers and books were consulted, because no-one is a specialist in all the 77 recognised families. Most decapod taxonomists specialise in one or few families (either hermit crabs, or some crabs or prawns).

Further reading

- Piers K. Dunstan, Nicholas J. Bax, Scott D. Foster, Alan Williams and Franziska Althaus (2012) Identifying hotspots for biodiversity management using rank abundance distributions. Diversity and Distributions: 18, 22–32.

- Piers K. Dunstan and Scott D. Foster (2011) RAD biodiversity: prediction of rank abundance distributions from deep water benthic assemblages, Ecography, Volume 34, Issue 5: 798–806.

- McCallum, A., Poore, G, Williams, A., Althaus, F., O'Hara, T. (2013) Environmental predictors of decapod species richness and turnover along an extensive Australian continental margin (13-35ᴼS). Marine Ecology

- Alan Williams, Franziska Althaus, Piers K. Dunstan, Gary C.B. Poore, Nicholas J. Bax, Rudy J. Kloser and Felicity R. McEnnulty (2010) Scales of habitat heterogeneity and megabenthos biodiversity on an extensive Australian continental margin (100–1100 m depths). Marine Ecology

- Gary C. B. Poore, Lynda Avery, Magda Błażewicz-Paszkowycz, Joanna Browne, Niel L. Bruce, Sarah Gerken, Chris Glasby, Elizabeth Greaves, Anna W. McCallum, David Staples, Anna Syme, Joanne Taylor, Genefor Walker-Smith, Mark Warne, Charlotte Watson, Alan Williams, Robin S. Wilson and Skipton Woolley. (2014) Invertebrate diversity of the unexplored marine western margin of Australia: taxonomy and implications for global biodiversity. Marine Biodiversity. Online publication date: 31-Jul-2014.

Images

Thumbnail images above

- Map of sample sites from the 2005 survey of Australia’s western continental margin (contour lines: 100 m (green) and 400 m (red). Image: CSIRO

- Example of seabed habitat and fauna: a large vase sponge attached to a reef outcrop at 106 metres depth off Ningaloo Reef. Image: CSIRO

This hermit crab may be Ciliopagurus cf. krempfi (Forest, 1952) and may represent a new record for Australia, or it may indeed be a new species. Image: Museum Victoria

Predicted evenness and species richness of seabed communities. Areas with high richness and low evenness (for example, solid red) are more likely to contain rare species. Image: CSIRO

Contact

Alan Williams, CSIRO

Gary Poore, Curator Emeritus, Museum Victoria

- Log in to post comments