February 15, 2018

An extensive, collaborative study by the Marine Biodiversity Hub has confirmed that shellfish reefs are one of Australia's most threatened ocean ecosystems, with 90–99 per cent of this beneficial and once-widespread habitat having disappeared.

The study, reported today in the journal PLOS ONE, was led by The Nature Conservancy and involved 15 scientists from 10 agencies in every state of Australia. It found that reefs formed by the Australian Flat Oyster have experienced the most dramatic decline, with only one of 118 known historical locations remaining, at Tasmania's Georges Bay. The second most severe decline of the 14 bivalve species studied was native Rock Oyster reefs, which remain at only six of 60 historical locations.

“We already knew shellfish reefs were in bad shape globally with 85 per cent of them lost or severely degraded,” Dr Chris Gillies of the The Nature Conservancy Australia says. “Now we know the situation for these important marine habitats in Australia is even worse, with less than 1% of Flat Oyster and 10% of Rock Oyster habitats remaining.”

Co-author of the paper, Dr Ian McLeod of James Cook University’s Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Research, says the loss of shellfish reefs is not well known because the reefs disappeared so long ago, during the 1800s and early 1900s.

The ocean’s engineers

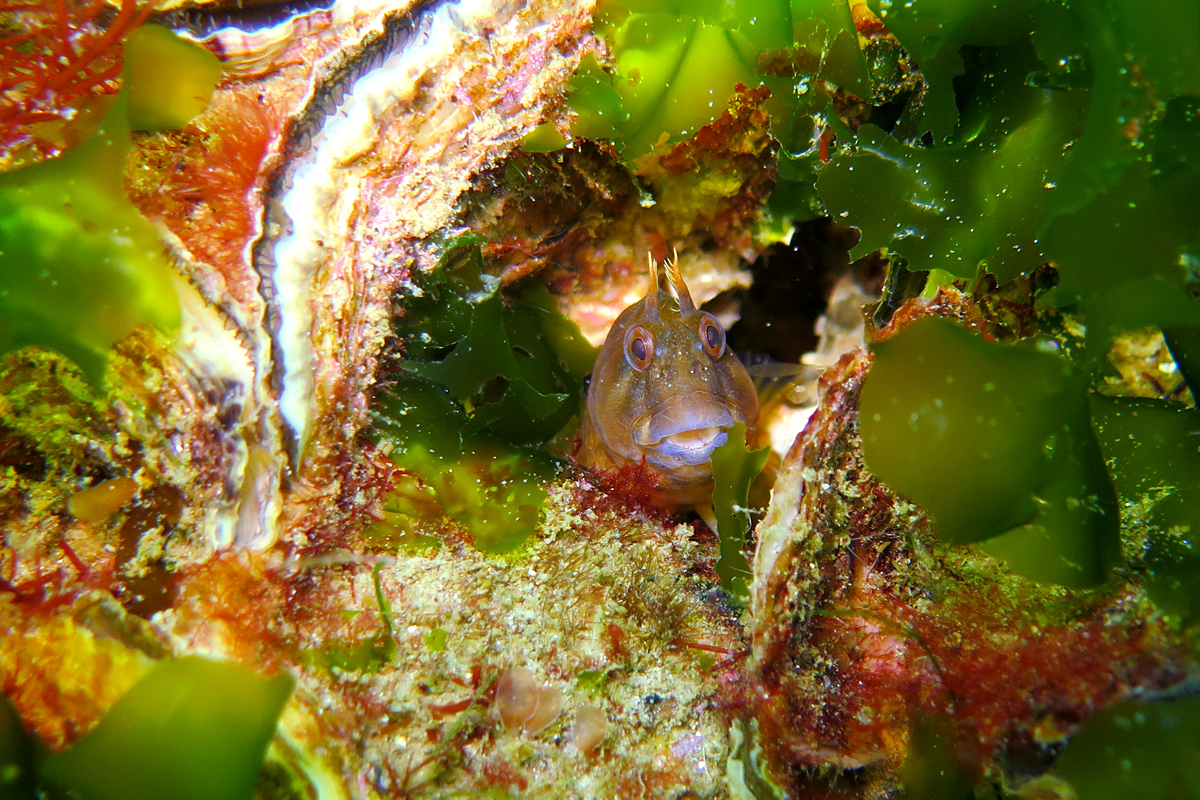

Oysters and mussels are ecosystem engineers that create, modify and maintain important habitat for a range of other species at a system-wide scale. When occurring in dense aggregations they form reefs and beds that contain unique biological communities. They also provide a range of ecosystem services such as food provision, habitat for fish and invertebrates, water filtration, fish production and shoreline protection.

The study highlights that the loss of these habitats negatively affects the economic and social wellbeing of coastal human populations, reducing the productivity of fisheries, increasing pollution risks to coastal communities and industries (such as aquaculture) and by increasing the cost of protecting coastal assets with built infrastructure such as seawalls. The degradation of coastal ecosystems also contributes to the release of stored carbon, worsening climate change and increasing coastal risks associated with more frequent and intense storms, sea level rise and ocean acidification.

Recommendations for restoration

Dr Gillies says there is still time to arrest the decline in shellfish reefs and restore them to places where they once bestowed all these benefits, provided the threats that previously destroyed them can be avoided. The main reasons for the reefs’ decline are overfishing for food and lime production (from the shells), destructive fishing practices (such as dredging), habitat modification, disease outbreaks, invasive species and a decline in water quality.

The study made three major recommendations to support the restoration of shellfish reefs:

- Educate the community on the function and value of shellfish ecosystems.

- Protect all remaining shellfish ecosystems and eliminate current and future threats by protection under Commonwealth and state government threatened ecological community, flora and fauna, and fisheries policies and legislation.

- Invest more in shellfish reef restoration projects.

Restoration in action

Australia is already well equipped to reverse the decline of shellfish ecosystems with a number of existing tools available to help protect and restore them.

Projects are planned or happening in every Australian state with the assistance of private, government and non-government funding. A national network of practitioners, The Shellfish Reef Restoration Network, has been established to help support reef protection and restoration.

The Nature Conservancy has shellfish reef restoration projects under way in Port Phillip Bay, Victoria; Gulf St Vincent, South Australia; and Oyster Harbour, Western Australia. At an eventual size of 20 hectares, Windara Reef in South Australia will be the largest shellfish reef restoration project in Australia.

Further reading

- Paper in PLOS ONE: Australian shellfish ecosystems: Past distribution, current status and future direction

Shellfish reefs restoration website

- The Nature Conservancy media release

- 19th International Conference on Shellfish Restoration & Shellfish Reef Restoration Network Meeting, 19-21 February, University of Adelaide, SA

- Log in to post comments