Dense, giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) forests were once ubiquitous off Tasmania, but now only five per cent remain and they are listed by the Australian Government as an endangered marine community: the first such listing for a marine community in Australia.

Active restoration of disappearing giant kelp forests represents one approach for their conservation. However, any restoration effort must consider the ongoing challenges and threat of ocean warming, which is the key driver of giant kelp forest loss. This project aimed to examine whether more thermally-tolerant giant kelp ‘genotypes’ existed among remnant giant kelps, and if so, to assess the use of warm-tolerant family-lines as the foundation of potential restoration efforts.

Approach

Reproductive material was non-destructively collected from 50 individual giant kelp across six remnant forests in eastern and southern Tasmania (these regions are the former stronghold of the species in Australia). These samples were used to establish giant kelp cultures in the lab, and the creation of one of the world’s first giant kelp ‘seed banks’.

Samples were taken from each of the 50 giant kelp cultures, and the resultant juvenile kelp were grown under a range of different seawater temperatures. Those that survived and grew best at higher temperatures were selected for further breeding and then outplanting.

The selected giant kelp family-lines were planted at three trial sites to test various methods of outplanting and also the survivorship of lab-grown giant kelp in the field. The ultimate goal of outplanting was to establish self-sustaining (and potentially self-expanding) patches of giant kelp.

One of the trial sites was selected in collaboration with a local Tasmanian Aboriginal Community who are custodians of local lands and waters, and interested in the restoration of their Sea Country. An additional aim is to train members of this community in kelp restoration practices once the outplanting methods have been refined

Results

All the tested giant kelp family-lines grew well at 12°C and 16°C, which are typical seawater temperatures in Tasmania. At warmer temperatures of 20°C, the majority of family-lines perished, however ~10% of the tested kelp survived and grew well at these temperatures. Surprisingly, some family-lines even survived at temperatures as high as 24°C.

Tolerance to warm water was not related to the site where the giant kelp were initially collected, and family-lines collected from warmer northern sites were no better at surviving higher temperatures than kelp collected from cooler southern sites. Equally, some of the giant kelp that survived at the highest temperature of 24°C were collected from cooler southern sites. The family-lines identified to be more warm-water tolerant were bred in large quantities, and the resultant juvenile giant kelp outplanted at the three trial restoration sites.

Two methods were trialled for outplanting, with the microscopic juvenile kelp seeded onto thin lines wrapped around elasticated cords or onto small plastic plates that were then bolted to the rocky reef within the patches.

Two of the trial restoration sites were revisited in early 2021: one showed no survivors while the other was very successful in the number, growth/size, and health of kelps in the patch. The site that failed to establish experienced excessive sedimentation and growth of filamentous ‘turf algae’ over summer. Due to seasonal limitations and COVID-19 restrictions, outplanting had to occur in warmer spring months, rather than during the natural breeding period of autumn/winter. This may have affected survivorship of the out-planted juvenile kelp at this site, although clearly it wasn’t an issue at the other site where healthy kelps are growing vigorously at high density from the microscopic outplants.

Impacts

- Giant kelp that are more tolerant of warm water have been identified within remnant populations, providing hope and the potential to ‘future-proof’ restoration efforts.

- Outplanting methods continue to be refined, and while success rates of outplanting have so far been limited, lessons have been learnt that are invaluable to the transfer of the giant kelp from the lab to the field as part of cultivation and restoration efforts.

- Additional work, which was initially unplanned for, led to the development of long-term low-maintenance storage methods and a ‘seed bank’ for Tasmanian giant kelp. This will aid future restoration efforts and also provides genetic conservation of remnant giant kelp.

- The work has led to greater understanding of kelp breeding techniques and optimisation of the methods used to grow juvenile giant kelp and support their complicated life cycle.

- This project has generated increased interest and public awareness about the status and loss of giant kelp forests in Tasmania, and provides a solid platform for future projects to extend the breeding and selection programs, and the refinement and upscaling of outplanting methods.

Key facts

- Under ideal conditions, giant kelp can grow 50 cm per day, although average growth rates of around 1 cm per day are more typical.

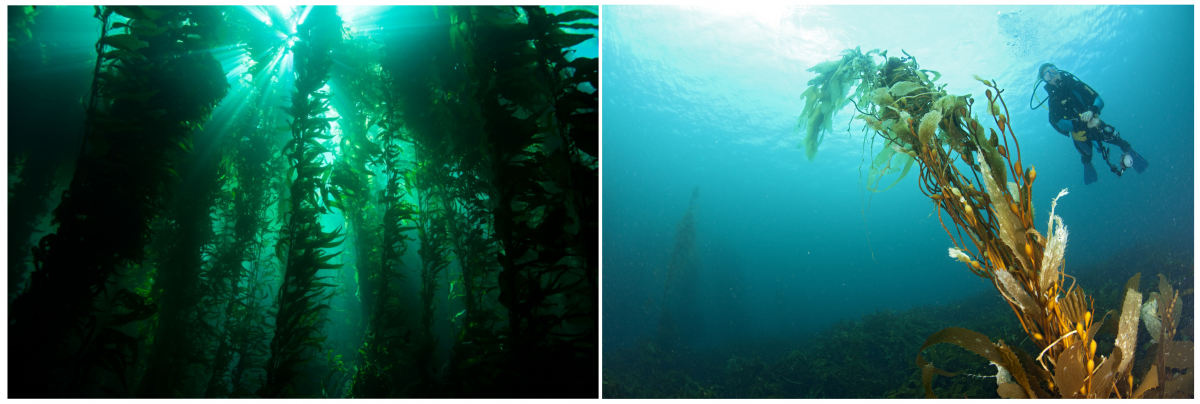

- Giant kelp forests create habitat for a large diversity of fishes, invertebrates, and other seaweeds.

- Southeast Australia is an ocean-warming hotspot, and waters in this region are warming more than 3 times faster than the global average.

- Kelp forests in southern Australia are the foundation of the Great Southern Reef (GSR). This spectacular temperate reef system is 8000 km long, and is a global hotspot of temperate biodiversity and endemism. Many of the species that live on the GSR occur nowhere else on Earth.

Related information