May 17, 2010

Gary Poore, Museum Victoria - CERF Biodiversity Program

Crustaceans (crabs, shrimps, lobsters and their many smaller relatives) are contributing to Marine Biodiversity Hub objectives in many ways. This is not surprising because these animals dominate many marine environments.

Crustaceans (crabs, shrimps, lobsters and their many smaller relatives) are contributing to Marine Biodiversity Hub objectives in many ways. This is not surprising because these animals dominate many marine environments.

Getting useful data from samples of crustaceans depends on being able to tell one species from another, in itself not a trivial task, and turning the resulting identifications into biogeographic and ecological patterns.

At least one third of the decapod species sampled from the continental slope of Western Australia are new to science. These collections now reside at Museum Victoria and we are actively promoting them for taxonomic and phylogenetic research. Already, a new species of shrimp (Bruce, 2008), two new spider crabs (Richer de Forges and Poore, 2008), and one new deepwater goneplacid crab (Ahyong, 2008) have been described. In progress are descriptions of eight new chirostylid squat lobsters and two new crested hippolytid shrimps by Anna McCallum, two new species of crangonid sand shrimps by Joanne Taylor, and at least ten species of axioid mud lobsters by me and research assistant, David Collins. Publication of these new taxa is expected by the end of 2009. This total of 26 out of the 200 new decapods doesn’t seem like much but we have promises from taxonomic experts to work up other groups in the future and will continue to chip away at the most speciose families. The old-fashioned taxonomic descriptions have a first objective of providing the language we use to talk about taxonomy. But more so, identifying animals as endemic or widespread enables biogeographic patterns to be understood. And, it provides the background against which the reality of molecular-based phylogenies can be assessed.

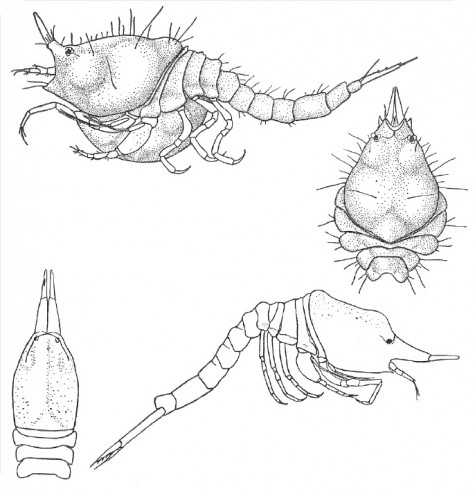

An important series of grab samples was taken along the WA coast during 2005 and 2007. These target the small invertebrates of soft sandy and muddy sediments. All recognisable animals have been now extracted in the laboratory and sorted to major taxon. (See the article by Robin Wilson on one of these invertebrates, the polychaete worms.) About half the animals are crustaceans, small amphipods, isopods, cumaceans, tanaidaceans and the like, individuals of the order of 3–5 mm long. During 2009, these are being identified to morpho-species. It is no surprise to us that while it is possible to place many in a known family and most in a genus almost none can be assigned a species name. The principal reason for this is that we are working in an unexplored environment and that previous taxonomic research on these taxa has been confined to eastern states or to shallow water. Museum Victoria has engaged expert taxonomists to help: Magdalena Blazewicz-Paszkowycz from Poland for tanaidaceans and Genefor Walker-Smith for the remaining groups. The objective is to seek biogeographic patterns and to correlate these with the physical and historical environment, so actual species names are not critical. The only similar study in Australia concentrated on isopod crustaceans (Poore et al, 1994). The preliminary data for Cumacea are indicative of what can be anticipated for other groups. Cumaceans have been relatively well studied taxonomically in South Australia and Bass Strait. The figures below are of species described in the 1930s by Herbert Hale and are similar, if not the same, as those from the WA material.

Top “Fig. 14. Nannastacus johnstoni, lateral view and dorsal view of cephalothorax of type female (x 56)”

Bottom “Fig. 9. Nannastacus nasutus var. camelus. Female; lateral view; dorsal view of cephalothorax (x 30)”

So far, at least 50 species of cumaceans have been distinguished. Most occur in only one, two or three of the more than 100 grab samples. This indicates once again that most species are either very rare or have limited distributions or are hard to catch. Our sampling is only beginning to gain an insight into total biodiversity but will be sufficient to explore gross patterns. It remains to be seen if these patterns mirror those shown by fishes or decapods or correlates with environmental variables. All of the crustaceans taken in these samples are brooders so differ in life-history strategy from decapods which have a planktonic larval stage.

References :

Ahyong, S., 2008. Deepwater crabs from seamounts and chemosynthetic habitats off eastern New Zealand (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura). Zootaxa, 1708: 1-72.

Bruce, A. J., 2008. Palaemonoid shrimps from the Australian north west shelf. Zootaxa, 1815: 1-24.

Poore, G. C. B., J. Just & B. F. Cohen, 1994. Composition and diversity of Crustacea Isopoda of the South-eastern Australian continental slope. Deep-Sea Research, 41: 677-693.

Richer de Forges, B. & G. C. B. Poore, 2008. Deep-sea majoid crabs of the genera Oxypleurodon and Rochinia (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Epialtidae) mostly from the continental margin of Western Australia. Memoirs of Museum Victoria, 65: 63-70.

- Log in to post comments