February 8, 2018

MEDIA RELEASE

Looking for brothers and sisters among juvenile white sharks has provided the final pieces of information needed to estimate the size of populations in Australian waters.

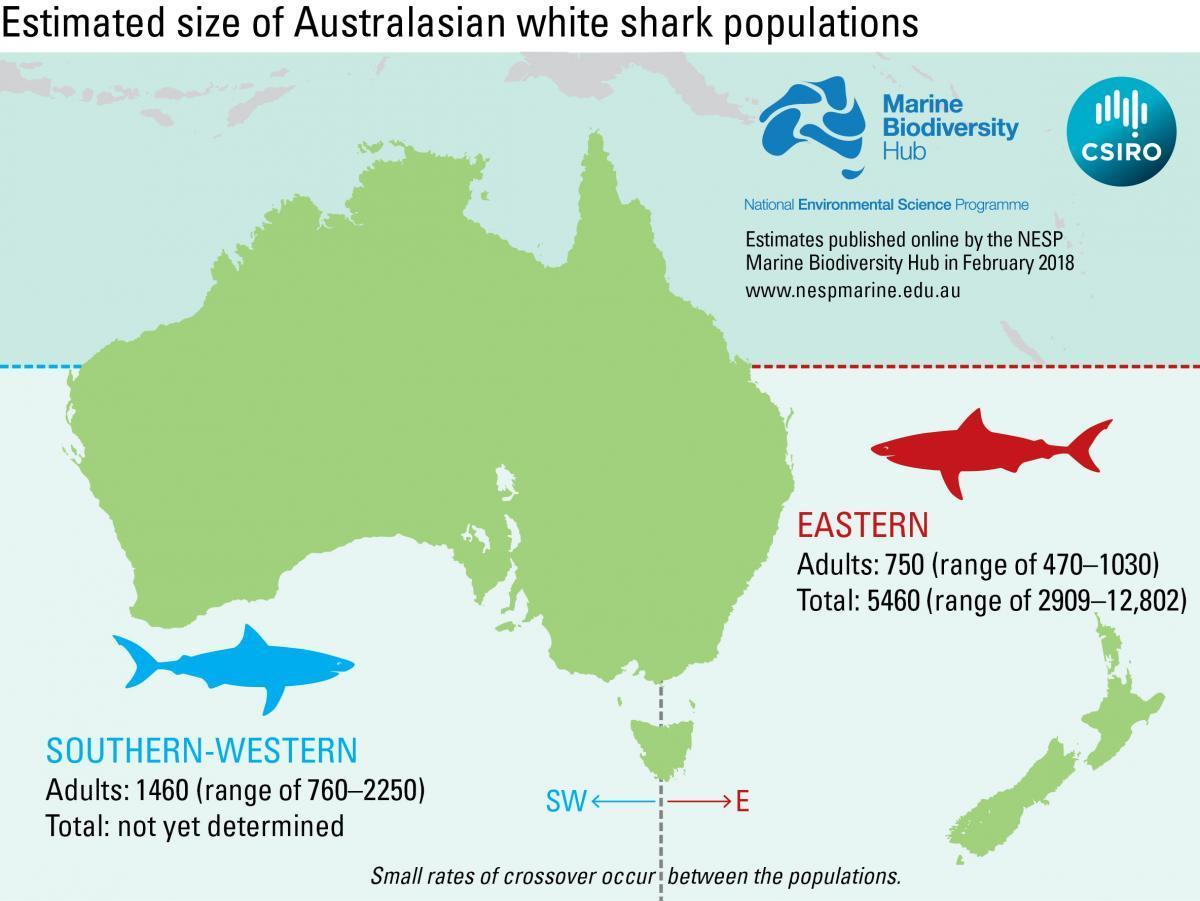

Australia has two white shark populations, an eastern population ranging east of Wilson’s Promontory, Victoria, to central Queensland and across to New Zealand, and a southern-western population ranging west of Wilson’s Promontory to north-western Western Australia.

CSIRO-led research funded by the Marine Biodiversity Hub indicates there are approximately 750 adults in the eastern Australasian white shark population (with a range from 470 to 1030), and about double that number in the southern-western population.

The research also reveals the total number of white sharks in the eastern population is 5460, with a potential range between 2909 and 12,802. The total population could not be calculated for the southern-western population.

Details of the research methods and sampling, in the context of the eastern Australasian white shark population, are published today in the journal Scientific Reports. A report detailing further research and providing the latest population estimates has also been published today by the Marine Biodiversity Hub.

The research has also provided important details on adult survival rates, which were very high in the eastern population, in the range of 90 percent and above. This means that for 100 sharks alive this year, 90 would be expected to be alive next year.

For the southern-western population, the 2017 estimate is 1460 adult white sharks with a range of 760 to 2250. The adult survival rate is also estimated at above 90 percent.

The abundance estimates have been made possible thanks to decades of teamwork by CSIRO and research agencies in New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia, Victoria and New Zealand.

Electronic tagging to track movements and survival, and biological studies to measure growth and breeding rates provided much of the information needed to model white shark numbers.

For example, juveniles fitted with internal acoustic tags by CSIRO and New South Wales Department of Primary Industries off NSW are tracked by a network acoustic receivers positioned along Australia’s eastern coast.

This network, coordinated by Australia’s Integrated Marine Observing System, monitors the juvenile sharks’ annual migrations, and how many survive from year to year.

Parental numbers found in the DNA of juveniles

Until now, information about adult white sharks has been elusive, because adults are very difficult to sample, particularly on the east coast. Thanks to a breakthrough in genetic and statistical methods, this problem has now been solved.

The breakthrough means scientists have been able to estimate adult shark numbers without having to catch or even see any adult white sharks. Instead, they located the tell-tale marks of the parents in the DNA collected from juveniles.

For the eastern population, researchers analysed DNA from 214 juveniles to find the genetic ‘marks’ of both parents. More than 70 individuals were found to share a parent, and this number has a statistical relationship to the total size of the adult population.

“The chances of any two juveniles in a population sharing a parent depends on how many adults are around to share the job of reproduction,” lead author of the paper, Dr Richard Hillary of CSIRO says.

“In a small population, more juveniles share a parent than in a large population, and vice versa.

“And as more juveniles are sampled over time, the parental marks we detect also reveal patterns of adult survival, which we determined to be greater than 90 percent in the east.

“We found many cases of parents (both male and female) that apparently had survived 20 or more years between the births of their children.”

Dr Hillary says population estimates for marine species generally require long-term datasets from sources such as fisheries catch records, but these don’t exist for white sharks.

“Other estimates have focussed on annual returns of sharks to particular sites, and extrapolated the results across entire regions, but there are challenges in these approaches that undermine their accuracy,” he says.

In the southern-western population, DNA samples were collected from 175 sub-adult and young adult males from Geraldton in WA to western Victoria. From these 175 samples, 27 were found to be half-sibling pairs (shared one parent).

The samples came from a variety of sources including necropsies of accidentally killed sharks, recovery of DNA from degraded tissues such as preserved jaws, and dedicated scientific sampling trips by CSIRO, the South Australia Research and Development Institute, Flinders University, and the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (Fisheries).

A total population estimate has not yet been compiled for the southern-western population because direct estimates of juvenile survival rates (a crucial piece of information obtained by tagging a relatively high number of juvenile sharks) are not available.

Adult populations have been stable since protection

Adult populations for both the eastern and southern-western populations were estimated to have been stable since the onset of white shark protection (at the end of the 1990s).

This is consistent with the long time it would take for the effects of the various control programs and levels of fishing that existed pre-protection (which focused mostly on juveniles) to flow through to the adult population.

Sharks take 12–15 years to become mature adults, so we wouldn’t expect to see the effect on the adult population of that reduction in juvenile shark mortality until the next few years.

Estimating the trend in total population size for both populations requires continued teamwork, sampling and analyses, using methods and institutional relationships developed in this project.

“Now that we have a starting point, we can repeat the exercise over time and build a total population trend, to see whether the numbers are going up or down,” Dr Hillary said.

“This is crucial to developing effective policy outcomes that balance the sometimes conflicting aims of conservation initiatives and human-shark interaction risk management.”

This work was undertaken for the National Environmental Science Program Marine Biodiversity Hub, an Australian Government initiative to provide information and understanding to support biodiversity management and conservation in the marine environment, with support from collaborators in New South Wales, Western Australia, and South Australia.

Media contact: Chris Gerbing, CSIRO, 0418 800 778, email Chris.Gerbing@csiro.au.

Further reading

- Paper in Scientific Reports: Genetic relatedness reveals total population size of white sharks in eastern Australia and New Zealand

- Article in The Conversation: World-first genetic analysis reveals Aussie white shark numbers

- Fact sheet: Assessing the size of Australia's white shark populations

- CSIRO media release: Sibling matches give scientists the gen on white sharks

- Technical report: A national assessment of the status of white sharks

- Log in to post comments