August 22, 2019

A Red Handfish hugs the seafloor, one fin resting on a palette of seaweeds in pinks, purples, browns and greens. With its grim expression, cocked illicium and helmet-like crest, this little gladiator looks set for battle.

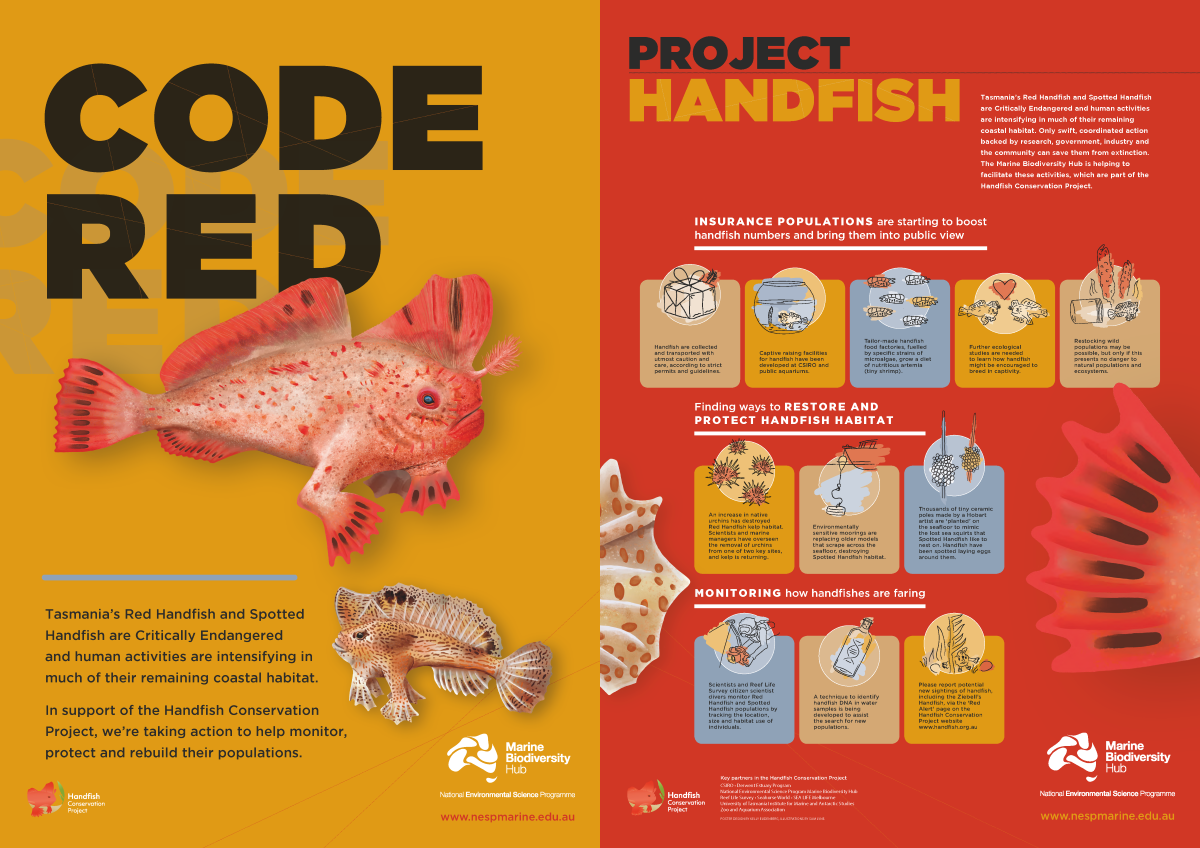

The handfish belongs to a small colony located at a shallow reef patch east of Hobart. The population was added to the map in early 2018, bringing the number of known Red Handfish colonies to two. Together they are believed to support about 100 adults, making Red Handfish arguably one of the rarest marine fishes in the world.

Coastal development and a changing environment have meant a war of attrition for the Red Handfish. But some hope is on the horizon. Scientists, managers, industry and the community are mobilising to help save the Red Handfish from extinction.

Vulnerable to change

The Red Handfish (Thymichthys politus) is one of 14 handfish species endemic to Australia, eleven of which are found in Tasmania. It was first described from a specimen collected at Port Arthur in 1844, and used to be locally common across south-eastern and northern Tasmania.

Little is known about the ecology and biology of Red Handfish, but they are thought to favour shallow rocky reefs that are at least partially sheltered from prevailing swells, usually in depths of less than 10 metres. The females lay relatively small egg masses in August–October at the base of seaweeds (such as Caulerpa spp.) or seagrass and stand guard until they hatch.

Unlike many marine species, which spend the early stages of their life as free-drifting larvae, Red Handfish hatch onto the seabed as fully metamorphosed juveniles 4–6 mm in length. This limits their capacity to ride the current; for populations to mix, or colonise new areas.

This life history strategy, combined with their reliance on shallow coastal habitats near urban and industrial areas, makes them highly vulnerable to change.

Their seaweed and seagrass habitats are degraded and face ongoing threats from pollution, excessive nutrients, warming seas, and ecological interactions associated with native sea urchins and their predators.

The native sea urchin has increased in abundance, possibly due to fishing activities that remove its predators, such as rock lobsters. The urchins form large aggregations and overgraze the seaweed on rocky reefs, creating ‘barrens’.

Collection for the aquarium trade also remains an ever-present concern, as any poaching could have drastic consequences on the number of breeding adults in such a small population.

Extensive surveys for Red Handfish in the past 15 years across the species’ former range have found only the two colonies at Frederick Henry Bay near Hobart, each occupying patches of reef no larger than a soccer pitch.

Joining forces for conservation

With their population so depleted, the Red Handfish is listed as Critically Endangered under Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and is protected in Tasmania.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species is being updated to recognise Red Handfish as Critically Endangered (at extremely high risk of extinction in the wild).

Research and conservation for the Red Handfish (as well as for the Critically Endangered Spotted Handfish and Ziebell’s Handfish) is coordinated by the National Handfish Recovery Team (NHRT) through the Handfish Conservation Project.

The team is chaired by the Australian Department of the Environment and Energy and includes the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (Tasmania), CSIRO, the Derwent Estuary Program, and the University of Tasmania Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS). The Marine Biodiversity Hub is helping to facilitate research and conservation activities.

A weighty decision

Divers from IMAS and Reef Life Survey surveyed the newly mapped Red Handfish colony at Frederick Henry Bay in early 2018 and have been keeping an eye on both colonies. In September 2018, an adult female was spotted guarding an egg mass, and a proposal to raise the juveniles in captivity to test the viability of ‘head-starting’ was put to the NHRT.

It was a difficult decision for the NHRT. The plan was risky, especially for a species with so few remaining individuals. But on the other hand, there are likely limited remaining chances to intervene.

Two key factors swayed the team’s decision to proceed.

First, there was no certainty that divers would find another Red Handfish egg mass, that year or in the future.

Secondly, the same collaborators had worked together in a previous project to successfully collect and rear Spotted Handfish, with ambassador populations now on public display at Tasmania’s Seahorse World and SEALIFE Melbourne. The systems, expertise and facilities were still in place and could quickly be made operational.

Tailor-made accommodation

In an operation led by Tim Lynch of CSIRO, the adult female Red Handfish and egg mass were collected in November 2018 and transferred to CSIRO according to collection protocols developed for the Spotted Handfish.

The Spotted Handfish holding facility at CSIRO Hobart was adapted to meet the different requirements of the Red Handfish, such as water chemistry, and habitat features and diet.

“While Spotted Handfish like open areas of sand, Red Handfish are reef species and prefer to be wedged in place, with one foot on a protective structure,” Dr Lynch says. “Reef, rocks and other animals were added to the tank, which was conditioned to provide the right biological environment and water chemistry.”

A special ‘food factory’ was built from scratch to produce the correct microalgae to grow a supply of artemia (brine shrimp) for the Red Handfish hatchling’s daily feeds. This called on the expertise of the Australian National Algal Collection, which is located very conveniently in the same CSIRO building as the aquarium.

“It was a nerve-wracking time and a scramble to get things organised, with ‘mum’ not eating her amphipods until her home was satisfactory,” Dr Lynch says. “In only two or three days, however, mum was happy and the eggs had started hatching.”

In December, 17 juveniles were transferred to a newly commissioned facility at Seahorse World, using transport procedures developed for the Spotted Handfish. To the relief of all who felt the weighty responsibility of keeping the Red Handfish alive, the intervention has so far been a success.

An added bonus has been the ability to show off the handfish to the public, and Seahorse World director Rachelle Hawkins is the person responsible for their ongoing captive care.

“To be asked to help raise the small number of Red Handfish babies hatched out at CSIRO labs, and to care for their mum, has been incredibly satisfying,” Ms Hawkins says.

“Our baby reds are on public display. They are simply amazing. Mama Red is off display, being kept in our quiet production area to minimise stress. In time, if she continues to show robustness in captive conditions, we may put her on display alongside her babies.

“The entire handfish display (juvenile Spotted Handfish, adult Spotted Handfish and the baby Red Handfish) is proving to be invaluable in explaining the plight of the handfish to the public during our guided tours.”

Giving handfish a head start

This achievement is potentially an important step towards boosting the population size of the Red Handfish in the wild. (Sixty Spotted Handfish have been returned to the wild following captive rearing.)

Juveniles can be ‘head-started’ by being reared in the aquarium beyond the highest stage of natural mortality (the first year of life) and released to ‘re-seed’ wild populations, and eggs can be collected each year to build up captive breeding stocks as an insurance population.

As part of the ‘head-starting’ approach, work has also been undertaken to rehabilitate Red Handfish habitat. A team of seven divers funded by UTAS removed 6000 urchins from a 50 m x 20 m area of shallow reef (3–5 m depths) at the most heavily degraded site.

"The cooperation between researchers from different research institutions, government agencies, and other stakeholders (including private businesses) has been unprecedented in my experience in managing threatened species," says Andrew Crane, Manager, Policy and Conservation Advice Branch, Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tasmania.

“In a very short time frame the team absorbed new information on threats to the red handfish and identified pathways to taking emergency action.

“The initial results speak for themselves, and it is no exaggeration to say that this cooperative effort has probably prevented the imminent extinction of this species – at least for the time being.”

Gathering intelligence

PhD student Tyson Bessell is working with IMAS and the Marine Biodiversity Hub to learn more about the ecology and biology of the Red Handfish, and how we might better conserve the species. He also aims to provide the world’s first formal population estimate of Red Handfish.

“In January this year, we undertook a dive survey of one of the Red Handfish sites,” Mr Bessell says. “We spent two long days searching, and photographed and measured every Red Handfish we saw. By doing this regularly throughout the year, we can try to estimate the population size.

“We’ve gone out to the field as much as we can, but in winter the water is too cold (9°C in July); we have intensive surveys planned for this spring and summer.”

Mr Bessell will also study Red Handfish movements, growth and habitat preferences, explore captive breeding techniques, and trial DNA testing of water samples, to make the job easier on scuba divers searching for new populations.

“These are important first steps towards conservation and recovery, and I hope my work can help save the Red Handfish from extinction,” he says.

Further information

- Read more about the Handfish Conservation Project and his work

- Request free copies of the Code Red handfish poster

- Tyson Bessell talks about his Red Handfish research: ABC radio interview

- Red Handfish Fact Sheet

- Marine Hub Researcher Profile - Tyson Bessell

- Log in to post comments