November 26, 2018

Day 4: Professor Nic Bax, Marine Biodiversity Hub, and Professor Thomas Schlacher, University of the Sunshine Coast

Day 4: Professor Nic Bax, Marine Biodiversity Hub, and Professor Thomas Schlacher, University of the Sunshine Coast

Humans have an enduring penchant and fascination with the rare and elusive. We desire diamonds more than river pebbles, are enchanted by the Mona Lisa slightly more than by Gazza’s brushstrokes in the shed, and pay considerably more money to trek after mountain gorillas then for spotting magpies in the park. Our fascination with rare animals is no different.

Rare and elusive animals are also the stuff of legends, mythical monsters, and towering literary works. Think of the Loch Ness, sailors’ frightening tales of giant squids and the Kraken of the abyss, and Moby Dick: the white whale of Melville’s epic tale pitching human avarice against the might of nature.

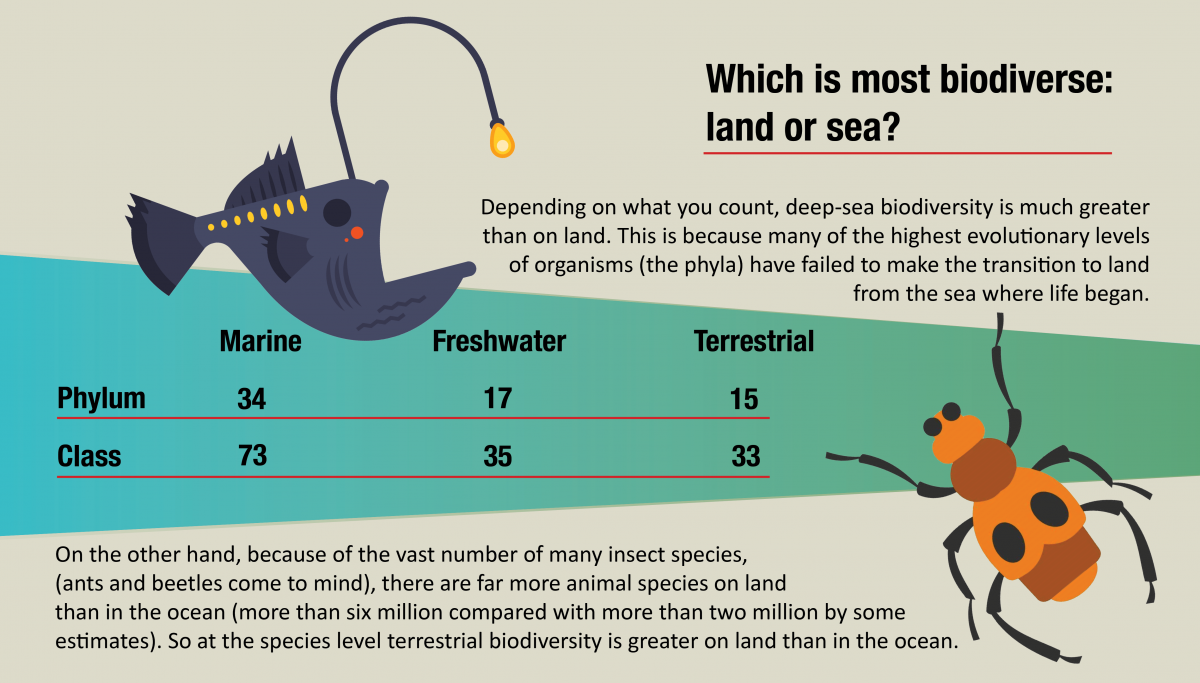

Perhaps nowhere is our fascination with rare animals greater than for denizens of the world’s deep ocean. But how rare are the creatures lurking in the ocean’s depth really? Surprisingly, the answer to this question is complex.

A common observation when sampling creatures from the deep seafloor is that we do not see most of them very often at all. In fact, half of the species recorded during a survey are likely to be only captured in a single beam trawl or in a single benthic sled. Here we have our simplest, and arguably most logical, definition of ‘rarity’: a single occurrence of an animal.

On top of this and depending on taxa and area being sampled, somewhere between 10 and 50 percent of the species collected will be new to science, creating both a lot of work for taxonomists, and raising a conundrum for ecologists: are these species really very rare? Is a species that is caught once on a single survey and very likely to be recaptured again in our lifetimes rare, or do we have a very restricted view of the diversity under our feet . . . in this case one to two kilometres under our feet.

While ‘a single individual’ is a rather attractive concept at first glance, it is biologically implausible: a lone (and likely lonesome) animal cannot reproduce and hence is doomed to extinction. It is also impossible for those sampling such lonesome creatures to decipher whether such apparent rarity is a real ecological phenomenon or an artefact produced by our sampling.

To examine this wicked problem of ‘apparent rarity’ (and it is a wicked one for many sampling the deep sea) we need to introduce two related aspects of rarity:

- an animal can be ‘rare’ because there are truly few individuals of it (its populations is small), and/or

- an animal can also be ‘rare’ because it only occurs in a small area (they have restricted ranges or distributions).

An ‘obvious’ solution to solve this wicked problem of ‘apparent rarity’ is to simply survey bigger areas of the seafloor, collect more animals, determine their species identify, and map out their ranges. This is all jolly fine in theory, but rather awfully complicated in practice.

The first challenge is the sheer size of the oceans, especially in the Southern Hemisphere where about 80 percent of our world consists of blue water and the seafloor beneath it. This stupendous expanse of the sea around us represents an enormous logistical challenge to every nation, including Australia, involved in deep-sea work. This comes into stark focus for us scientists on board when we view the tracks made by the ship overlaid on a chart: it somewhat resembles scrawls made with a very fine pencil on a gigantic canvas. The reality is that the vast majority of the deep ocean floor remains unknown to biologists: rare animals can abound and remain mostly uncollected.

Our limited sampling coverage of the deep ocean can produce two artefacts of rarity: we simply have not collected individuals that are actually widespread because we have not surveyed their habitat or range (that is, we ‘missed their spots) and/or we have not collected animals that are abundant because our techniques and equipment does not bring them on board.

It is technically difficult to capture many deep-sea animals effectively. For example, trailing a small net several kilometres behind and several kilometres under a vessel seems a bit like running at night through a rainforest with a butterfly net behind you on a long string: how many butterflies and beetles will you collect?

The challenge of sampling becomes even greater if you are tasked to map and count large and mobile animals; clearly, nets will not work well for giant squid, deep-sea sharks, and other spectacular animals (returning to the rainforest analogy: population counts of cassowaries and okapis rarely use butterfly nets ). We can use cameras, either towed behind a vessel or mounted on submersibles, and underwater microphones (useful for whales), but if encounter rates with big rare animals are very low, these techniques are also inefficient. Thus, we must be humble and acknowledge that many a rare deep-sea denizen may simply evade us in many cases.

All of the above may leave you with the impression that rare animals are rare because we rarely collected them in the right places. Some of that does come into play, but there is no reason to believe that rarity is truly uncommon. We have excellent examples of rare birds (a group that is exceptionally well mapped) and hence are confident that not all animals are created equal when it comes to abundance and size of distributions. We also have records of rare deep-sea fish which have been trawled for many decades (but new species continue to turn up all the time).

True rarity continues to fascinate and determining its true causes is a rare treat for deep-sea biologists.

Notes on today's activities from Marine Biodiversity Hub Director, Nic Bax . . .

The day started with the return of the beam trawl that had been deployed for a tow across the southern flank of Pedra seamount targeting the area where octocorals had been seen on the video at about 1000 m. Nearly 20 octocoral species were retrieved in good condition, including many that were undescribed species. Only four could be positively identified onboard. The remaining species will need further work back at the museum, illustrating the taxonomic challenge of research in this biodiverse area. Many brittlestars and polychaetes were retrieved in association with the corals. A variety of molluscs and urchins and one small black shark. All specimens were photographed so that taxonomists have a picture of the animals when fresh to link to the preserved specimens, including the animals they were associated with (such as brittlestars and polychaetes on the coral matrix).

Some additional work on the camera winch provided the opportunity to complete two multibeam swath transects in the area between the Huon and Tasman Facture marine parks, so that we will have full bathymetric map of this area at fine resolution. We returned for a our second towed video on 'Z16' seamount which ended up starting a bit before the summit, requiring some nimble camera operation to ascend alongside what looked like an almost vertical cliff covered with deep-water corals before starting the regular transect from peak to base of this coral-covered seamount. Coral cover became sparse beyond 1300 m, although we did spot an isolated colony close to 1500 m.

After one more uneventful tow on Z16, we transferred our attention back to Pedra to tow one of the legacy transects that we previously surveyed 10 years ago, followed by a tow on a parasitic cone named Mongrel because of rugged nature that makes it almost unfishable, unlike Pedra which has been trawled frequently. The deepwater coral, Solenosmilia was noticeably absent in both areas. Numbers of orange roughy were seen on both tows, especially Pedra. Stretches of what looked to be Crocoite, the state mineral for Tasmania was seen at the top of Mongrel.

- Log in to post comments