June 2, 2017

Day 19: Marc Eléaume, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France

Day 19: Marc Eléaume, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France

Crinoids, feather stars and sea-lilies, are delicate animals that belong to a larger group of animals called echinoderms (spiny skin). That means that crinoids are closely related to sea urchins, sea stars, sea cucumbers and brittle stars.

Crinoids have been around for 500 million years and were once very abundant, forming meadows of windmill-like animals that are now part of calcareous rock formations called calcaires à entroques. These are easily recognisable because they include star-like figures, or ossicles, that once formed the stalks of triassic crinoids.

Triassic crinoids have long vanished from the surface of the earth, but some of their descendants still thrive today. They are often called sea lilies because of their resemblance to plants. Indeed in 1761, the researcher who made the connection between the entroques and the ossicles that form the stalk of some crinoids, Jean Etienne Guettard, called them palmiers marins (or marine palmtrees).

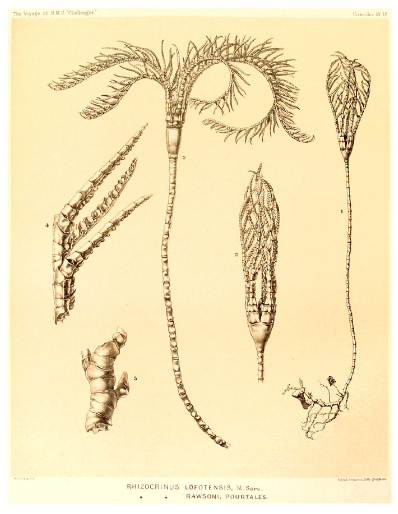

Sea lilies and feather stars are found everywhere, in every ocean (except the Baltic Sea) at depths ranging from 0 metres to 9000 m. There are about 700 species, and counting. Sea lilies display a stalk that anchors the animal to the substratum. The stalk can bear verticilles called cirri that help the animal cling to rocks or other organisms. These species are vagile (free to move about) and can crawl using their arms, dragging their long stalk behind them, on the sea bed.

Stalks in other species are often cemented to the substratum by way of a holdfast. Others still may develop root-like structures to anchor themselves in loose substrata. The stalk supports a crown of arms fringed with pinnules that ressemble feathers of a bird. This crown of arms is in fact a collecting apparatus that the animal deploys, downstream of the current flow, to capture small particles in suspension in the water.

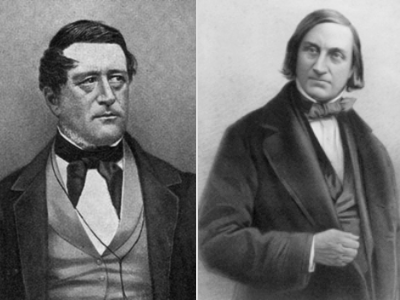

Stalked crinoids, as it happens, were the trigger for deep sea exploration. How is this you ask? Well, it all started with Edward Forbes, a talented British naturalist, who explored the Aegean Sea in the 1840s. Forbes did a number of dredging operations and found that diversity was decreasing with depth, leading him to postulate that no life was to be found deeper than 550 m. This is what has been coined as the azoic theory. Later in the 19th Century, the Norwegian Mickael Sars dredged animals from deeper than the azoic limit. Among these animals were specimens of Rhizocrinus lofotensis, a small 10-armed stalked crinoid that had never been collected before.

Charles Wyville Thomson, an influencial British naturalist and a crinoid expert, made aware of Sars findings, started deep-sea dredging on board the HMS Porcupine and Lightening. He found life thriving at depths greater than 550 m and down to 1200 m, refuting the azoic theory and starting a new era of marine research that eventually came into being with the HMS Challenger expedition, led by CW Thomson, that explored the deep ocean all around the world between 1872 and 1876.

This genus belong to a group of crinoids that are known to dwell in the deeper ocean, down to 9000 m, and, as it happens, includes R. lofotensis. They are generally small and slender with a very delicate crown of arms. It is rare that these animals arrive on deck intact. They generally lose parts and in the first place their arms. Often we know these animals from a stalk or part of a stalk. But here, we collected several specimens almost complete, displaying most of the stalk and part of the arms. These findings are exceptionnal, and will add to our knowledge of this ill-known group of animals, more than a 150 years after Mickael Sars collected the first of them.The deep ocean remains remarkably unexplored. Anything as deep as 4000 m has strong probabilities to be new to science. During the abyssal cruise onboard the CSIRO RV Investigator, we have collected a number of specimens of crinoid that have 10 arms, a stalk composed of elliptical ossicles, and a root-like structure to anchor in the muddy environment they live in. I have attributed these specimens to the genus Monachocrinus.

- Log in to post comments