June 3, 2017

Day 20: Asher Flatt, onboard communicator, and Izwandy Idris, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu

Day 20: Asher Flatt, onboard communicator, and Izwandy Idris, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu

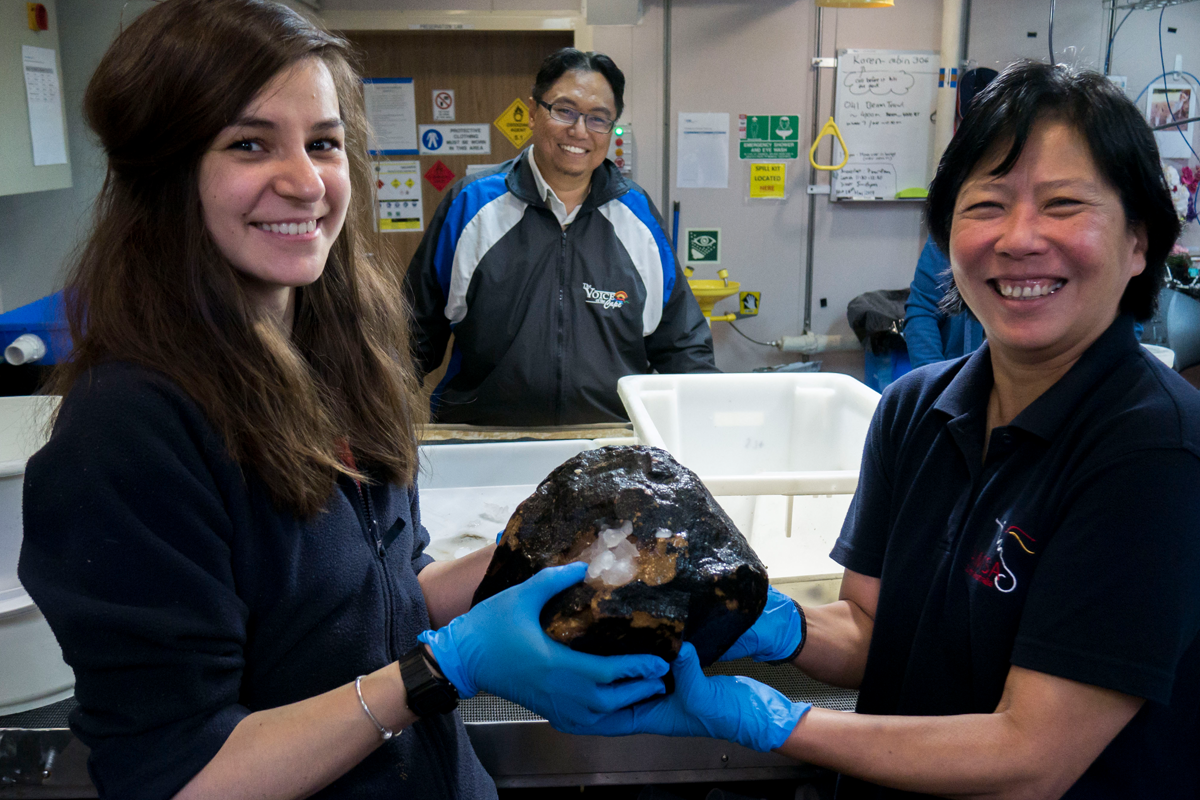

The CSIRO RV Investigator voyage to Australia’s eastern abyss is primarily a sample-gathering expedition from an almost entirely unknown region of Australia. The seafloor is mapped using multibeam sonar so that specialised equipment can be sent to retrieve myriad lifeforms from the abyssal plain. Then the hard work begins. Above the water and waves, in the science labs of the ship, all the samples (even rocks!) are sorted and catalogued to be sent to museums in Australia and around the world.

Sorting the catch ─ from beam trawl, Brenke sled and box corer ─ is an arcane art of mysterious symbology and lined paper, unknown to all but the most fastidious of minds. First, check the board outside the operations room for information on the daily operations. Second, turn on the ice machine so there is a good supply of iced seawater to keep all the abyssal beasties cold and fresh. Also prepare chilled filtered seawater in the fridge to accommodate surface, or planktonic, species. Third, prepare the sorting trays and weigh them before and after to tally total biomass. We are now ready to retrieve our samples!

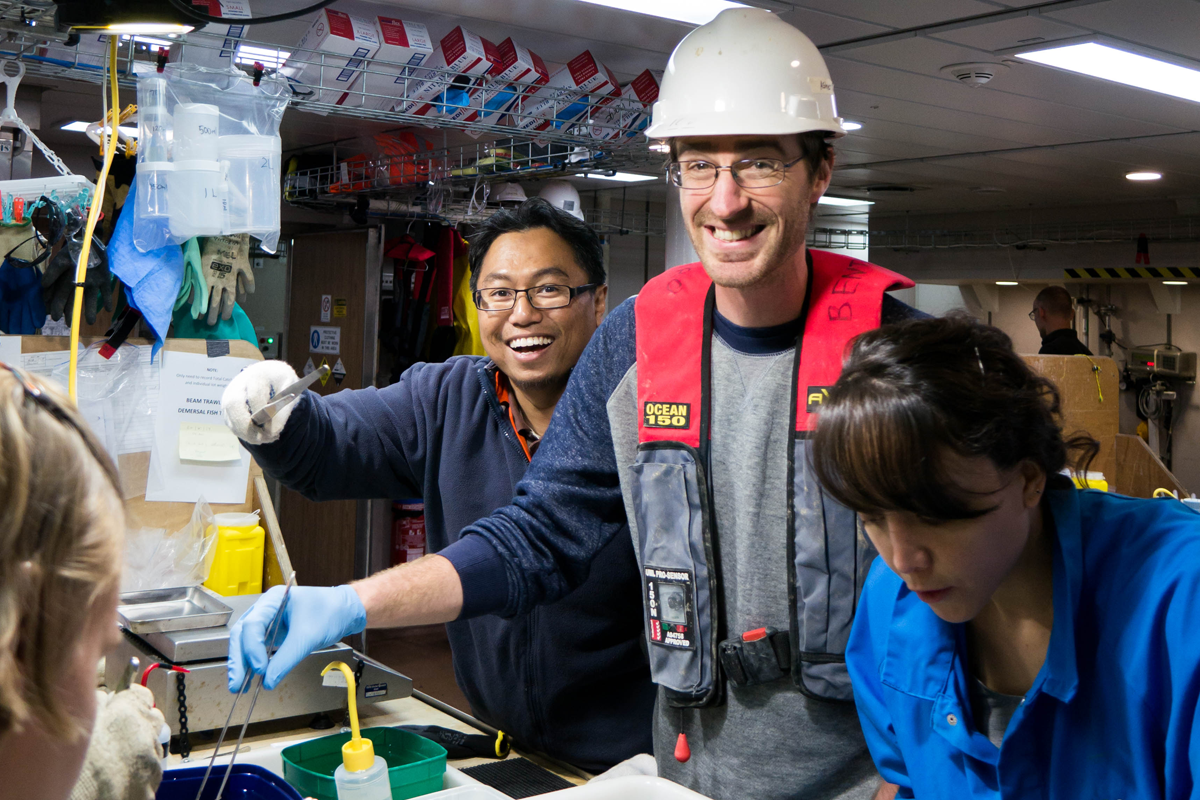

The rest of the science crew will be hanging back in the wings, waiting to put things on ice and quickly ferry precious samples back and forth from the deck into the lab. The collecting process needs to be done quickly yet carefully: the organisms are now out of water and some of them may possess sharp or venomous spines, and we also want to avoid damaging them. Keeping animals cold in containers of ice is very important at this stage. They have made the journey from the frigid abyssal depths to our alien world of light and warmth. If not kept cold, they will quickly lose their shape.

Now the sorting frenzy begins! First, all the animals are placed into general categories, such as sponges and starfish (refer to our previous Kombi post for more details!) then into more specific categories of the lowest possible taxa (family, species, or just a common group, such as Gastropoda.

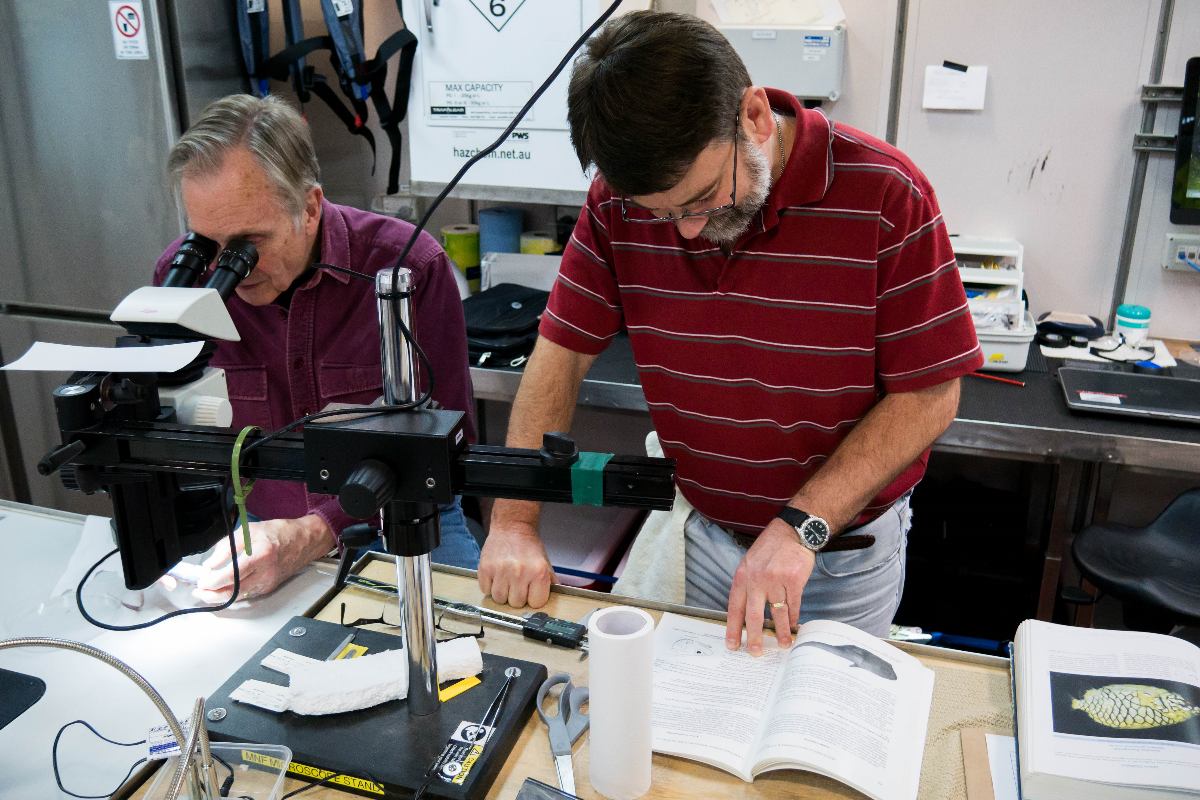

In the meantime, smaller samples from the Brenke sled will be graded by size and sieved to remove the remaining mud. Before this, a certain amount of samples will be put aside to be inspected for microscopic foraminifera. The cleaned samples are then sorted using a stereo microscope (remember the ship is continuously rocking!).

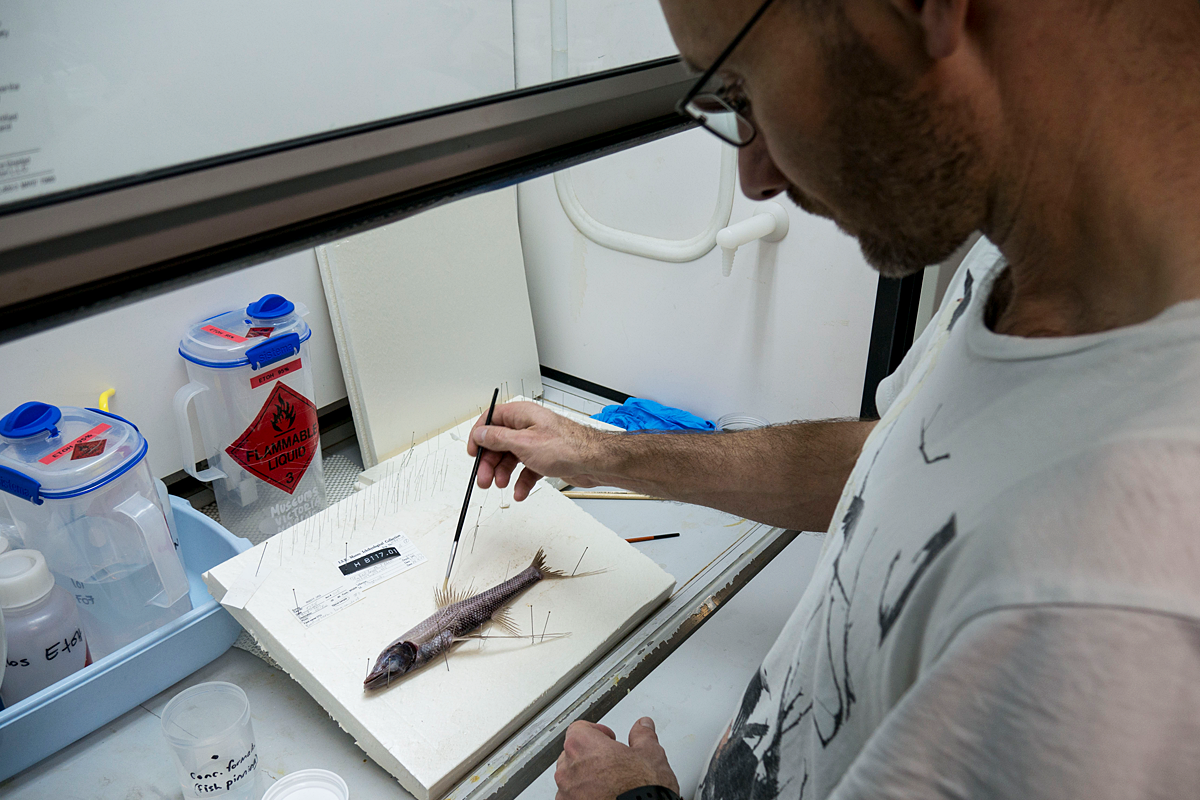

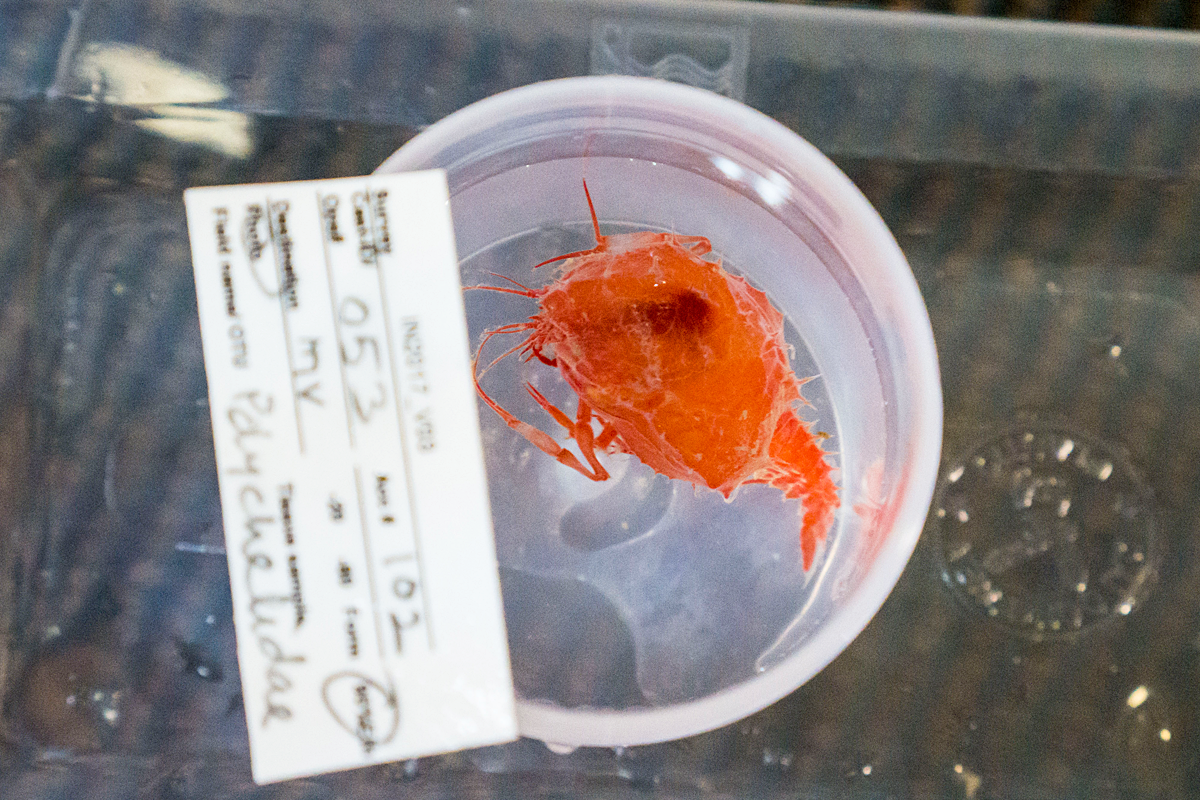

Special finds are photographed by Karen Gowlett-Holmes (invertebrates), and Alastair Graham and John Pogonoski (fish). Specimens, along with lengthy taxonomic information (identification numbers, destination, weight, preservation method etc.), are then listed in a records sheet. Correct labelling is very important. To avoid missing labels (a great sin for a biologist!), two levels of labelling (internal and external) are made. The internal label is made using special paper that can withstand ethanol or formalin solutions, and the external label is written with marker pen.

The samples and their papers are then sent to the aptly named 'pickler': the person in charge of placing our placid ocean pals in ethanol, formalin, or frozen: whatever other medium best prolongs the slow decay of time.

With this careful processing they can be available for reference and research for years to come. Finally the preserved specimens are boxed for sending to museums and institutions around Australia and even the world! While most specimens will be sent to CSIRO, Museum of Victoria, a numbers will go to Australian Museum, Geosciences Australia, Queensland Museum, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, and Natural History Museum, UK, and University of Vienna for further works after the voyage ends.

Sounds easy? Well, sometimes we have to spend the whole shift just processing specimens from one deployment. In other instances, three deployments were made within a 12 hours shift!

- Log in to post comments