May 21, 2017

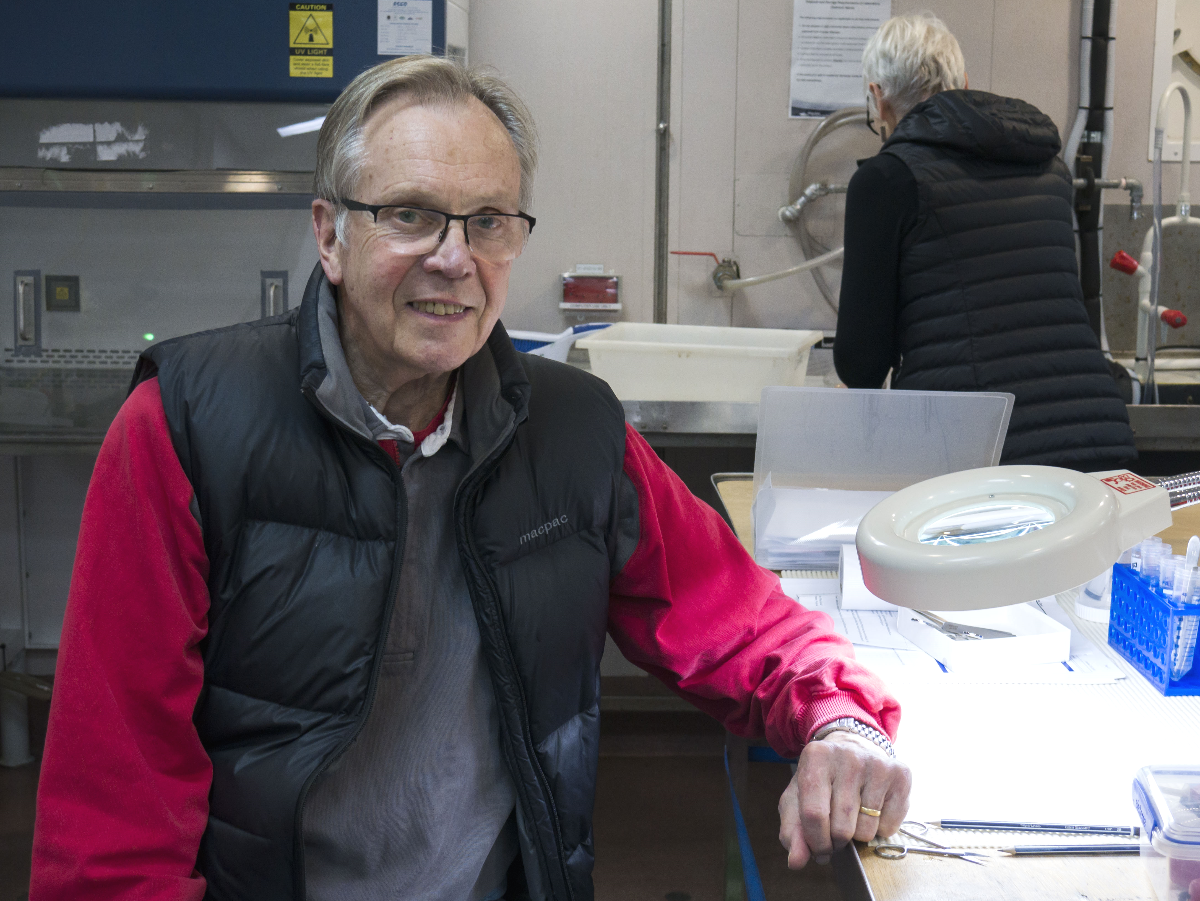

Day 7: Martin F. Gomon, Museums Victoria

Day 7: Martin F. Gomon, Museums Victoria

‘Deep-sea fishes’ conjures up thoughts of species with enormous fang-like teeth, rows of coloured lights and peculiar structures like fishing rods tipped with glowing lures. However, these are really the twilight dwellers inhabiting waters well above the bottom, depths to little more than a mere 1000 metres or so. Their evolution has been driven by the necessity of acquiring a meal in a food poor environment and at the same time avoiding becoming one for a fellow midwater traveller. Many living at these depths are daily migrators moving upwards at night under the cover of darkness to near surface waters where food abounds and once again back to the dimly lit depths below during the day to escape being seen.

The true abyss is many thousands of metres farther down where animals and their meals are generally far less distinctive, though similarly few and far between. Here the food pyramid is based on the bodies of animals, tiny to whale-sized, that have died in waters above and have slowly drifted to the abyssal floor. There, life’s energy is recycled by boneless scavengers that in turn provide meals for lethargic predators, conserving their energy as they go about a constant routine of acquiring what is needed in a timeless, lightless world.

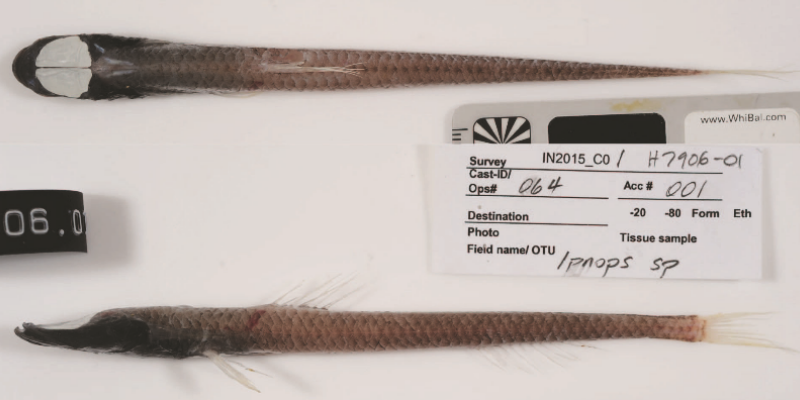

The vast majority of fishes living at abyssal depths have come from ancestors that arose early in the evolution of living fish lines, so that the more recently evolved bony fishes we are familiar with in shallow inshore waters do not feature. Instead, we find primitive eels and eel-like relatives, such as the spineback and prickleback eels with a row of unconnected spines along the back and small rabbit-like mouth, elongate cod-like cusk eels and their live bearing relatives the brotulas, and the ubiquitous rattails and whiptails that populate near-bottom areas throughout the oceans’ greater depths.

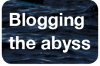

Although many have a rather boring generalised form, some abyssal species have acquired more striking modifications that allow them to do it better. Among the most iconic are the descendants of shallow water lizardfish-like ancestors, the tripod fishes that prop themselves above the bottom on extended rays of their paired pelvic fins and tail. Positioning themselves in slow moving bottom currents they direct their head toward the oncoming water with jaws agape to filter suspended food particles with comb-like gill rakers, which function like the baleen of much shallower feeding whales at the other end of the size spectrum.

Without the need of searching for a meal, tripod fishes no longer require visual acuity in this lightless environment as evidenced by their tiny degenerate eyes. Danger is detected rather by extended pectoral fin rays held away from the sides like the spokes of an umbrella constantly sensing for swimming vibrations emanating from an approaching predator. The detection system compliments their well-developed lateral line designed to do the same.

Closely related is the oddly named 'Grideye Spiderfish' having fins of a normal size but with a pair of large, greenish yellow oval plates on the upper surface of the head replacing eyes. The function of these plates is still to be fully understood. The plates are known to be light sensitive, but lack the internal structures needed to form a detailed image. As for many other inhabitants of the abyss, there is still much to be learned about these fishes.

- Log in to post comments