May 31, 2017

Day 17: Dianne Bray, Museums Victoria

Day 17: Dianne Bray, Museums Victoria

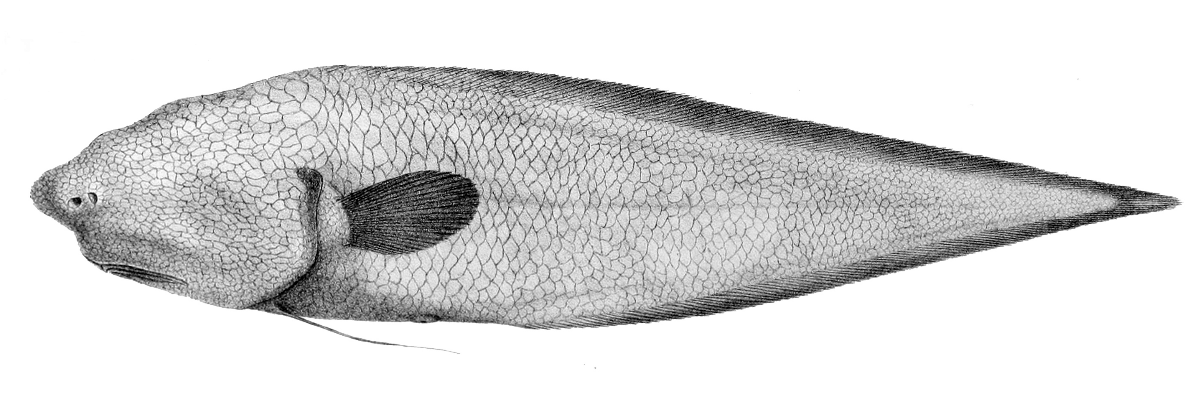

A large, weird faceless fish landed on the deck a couple of days ago. By faceless, I mean it had NO EYES – NOTHING – not even tiny spots or modified areas indicating eyes beneath the skin. It came from 4000 metres below the surface, where pressures are huge, the water is a mere 1⁰C, and the seafloor landscape is pretty barren!

Everyone was amazed. We fishos thought we’d hit the jackpot, especially as we had no idea what is was – some sort of cusk eel, kind of . . . Tissue samples were taken (for genetic analyses) and images were emailed to experts who work on weird abyssal fishes. We even conjured up possible new scientific names!

Until . . . my colleague and eel expert, John Pogonoski, of CSIRO’s Australian National Fish Collection, found something similar while working his way through various scientific publications. There it was – a cusk eel with the scientific name Typhlonus nasus. The word Typhlonus is apparently derived from the Greek, typhlos (= blind) and onos (= hake) – a blind hake!

So, it’s not a new species, but it’s still an incredibly exciting find, and we think ours is the largest one seen so far. Although very little is known about this strange fish without a face, it does have eyes – which are apparently visible well beneath the skin in smaller specimens. I doubt they’d be of much use though, so we’ve decided to call it the Faceless Cusk.

Although rare, it’s quite widely distributed, and is known from the Arabian Sea, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Japan and Hawaii – quite something for a fish living at depths between 4000 to 5000 metres. In 1951, one trawl in deep water off East Kalimantan, Borneo, collected five specimens, so perhaps we’ll find another as we move further north.

One of the really neat things about this strange fish is that it evokes the spirit of the Voyage of HMS Challenger, the world’s first round the world oceanographic expedition. Typhlonus nasus was first collected on 25 August 1874, from a depth of 2440 fathoms in the Coral Sea just outside what is now Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone.

The Challenger headed south from Portsmouth, England, on 21 December 1872, with 243 officers, scientists, and crew aboard. After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, she sailed across the Indian Ocean into the Pacific, passing Australia on the way, before surviving the seas of Cape Horn on her way back to England. Sounds simple when put that way. But it was gruelling!

We’ve had a few challenges surveying this abyssal plain off eastern Australia. It’s no easy task working at great depths, and at times we’ve come up against an angry seafloor with huge boulders and canyons. Deploying and retrieving our collecting gear from 4000 metres is a skilful operation that takes five to six hours and involves paying out more than seven kilometres of wire. So just imagine the effort it must have taken for the Challenger's crew to trawl down to 6000 m depths using piano wire, without our high-tech winches and computers! (See more about the Challenger expedition, and the first true map of the world's ocean basins in the blog: 'Sounding out a world of hidden folds and valleys beneath the waves'.

The Challenger expedition lasted four years, gathering a wealth of data and specimens from 362 different locations along the way. If you’re interested, the narrative of the voyage is available online at http://archimer.ifremer.fr/ just search on the year 1885. It’s a great read!

- Log in to post comments